Arizona National Guard Corruption

I don't know what the National Guard is supposed to do, but from these articles it sure sounds like we don't need it.On the other hand if you are a criminal that enjoys stealing stuff, raping woman and bullying people it sounds like the National Guard is a great place to get a job.

This is a link link to the series of articles.

About 'Letting down the Guard' series

SourceAbout 'Letting down the Guard' series

by Dennis Wagner - Oct. 13, 2012 11:45 PM

The Republic | azcentral.com

The Republic series, "Letting down the Guard," began when several high-ranking Arizona National Guard officers approached reporter Dennis Wagner with allegations that corrupt conduct had spread within the military organization because of lax discipline and leadership failures.

During a five-month investigation, The Republic employed sources and Arizona's public-records law to obtain more than a dozen military investigations, police reports, court files and other records. Wagner also spoke with at least 30 present or past Guard members, as well as outside experts on military affairs and ethics. Maj. Gen. Hugo Salazar, the Guard's adjutant general, was interviewed in person and via e-mail.

Early this month, The Republic submitted questions about its findings to Gov. Jan Brewer's office. Through a spokesman, the governor announced plans to commission a full, independent review of National Guard operations and disciplinary practices.

Allegations against National Guard uncovered

SourceRepublic special report: Allegations against National Guard uncovered

by Dennis Wagner - Oct. 13, 2012 11:48 PM

The Republic | azcentral.com

A five-month investigation of National Guard conduct and culture by The Arizona Republic has uncovered a systemic patchwork of criminal and ethical misconduct that critics say continues to fester in part because of leadership failures and lax discipline.

According to interviews with military officers and records obtained by The Republic, Arizona Army National Guard members over the past decade engaged in misbehavior that included sexual abuse, enlistment improprieties, forgery, firearms violations, embezzlement, and assaults.

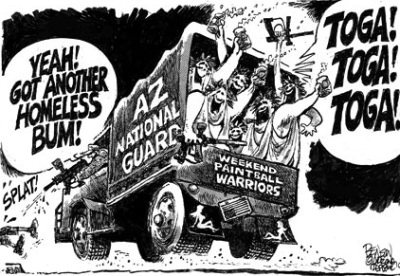

The wrongdoing, most of which has not been previously disclosed, was concentrated among military recruiters who often visit high schools in search of teenage recruits. National Guard investigators found that non-commissioned officers, known as NCOs, engaged in sexual misconduct, collected recruiting fees to which they were not entitled, forged Guard documents, and committed other offenses such as hunting the homeless with paintball guns.

Investigators asserted that National Guard commanders failed to hold subordinates accountable, in part because many supervisors also engaged in unethical behavior. Many high-ranking officers contend an atmosphere of disdain for discipline persists.

After The Republic shared its findings with Gov. Jan Brewer's office, she announced plans for a wide-ranging inquiry directed at Arizona military operations by a high-ranking National Guard officer from another state.

"The governor is calling for a full, fair and independent review of the Arizona National Guard, its operations, the personnel and discipline handed out in response to some of these incidents," said Matthew Benson, a spokesman for Brewer.

The National Guard is a state organization of more than 9,000 military and civilian personnel serving their state and nation. Most are part-timers assigned to weekend duty. Corruption and other misconduct appear to be confined to a small minority of the roughly 2,300 soldiers and airmen who are full-time employees. Many of these were in the Army National Guard Recruiting and Retention Command, according to The Republic's review of more than a dozen military and police reports.

Maj. Gen. Hugo Salazar, the Arizona National Guard's top officer, said in an interview that a rogue atmosphere in recruiting was detected and quietly addressed in the past few years.

"I acknowledge there was a problem," said Salazar, who has been adjutant general for four years and was second in command before that. "We should have had more command emphasis. We should have paid more attention ... It would be ridiculous of me to say we are not going to have some misconduct in the National Guard. We have people who do stupid things. (But) I do not believe we have an ongoing problem in the National Guard."

Salazar was appointed by Brewer as the Guard's top officer, or adjutant general, in April 2009 to complete a term that expired this April. Because of a change in Arizona personnel law this year, he now serves at the pleasure of the governor with no set term, Benson said.

Salazar said recruiting operations were reorganized with greater command oversight, and the most culpable soldiers were discharged or demoted. Training has improved, all misconduct reports are investigated and officers strive to mete out appropriate discipline.

In an opinion article published in The Republic Monday, Salazar emphasized the good service of Guard members and said "it would be a gross injustice if the mistakes of a few individuals were used to impugn the character and service of the entire Arizona National Guard."

But other high-ranking officers who talked with The Republic disagreed that problems have been dealt with. They said the National Guard suffers from lax discipline, cronyism, cover-ups, whistle-blower abuse and other systemic flaws. To this day, they note, the Guard has never successfully court-martialed an officer or soldier despite serious wrongdoing uncovered by investigators.

Lt. Col. Rob White, who conducted a command climate investigation in 2009 to assess whether commanders were at fault, said he is sickened by the failure of National Guard leaders to root out misconduct and impose punishment.

"The way the Arizona National Guard is today, I would not trust it with my son or daughter," said White. "It disgusts me ... People don't get fired, they get moved."

White, who oversees future operations at the Guard's Arizona Joint Forces Headquarters, is a soldier of 23 years with a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star. He and others said attempts at reform have repeatedly failed, in part because appeals to Brewer or the National Guard Bureau's inspector general have been simply referred back to Arizona Guard headquarters.

"The organization is there to take care of soldiers. That's what we're supposed to do," White said. "But what they're doing is taking care of good ol' boys. And, when victims come forward, the Arizona Guard turns on them and eats them."

Benson, the governor's spokesman, said Brewer remains confident in Salazar but believes an in-depth inquiry is needed. "If you're going to get to the bottom of something like this," he said, "you have to bring in somebody from the outside."

A few bad apples?

White and several other officers came to The Republic with their grievances out of frustration that the problems were not being addressed. Others shared their views confidentially for fear of losing their jobs.

"I'll probably get retaliated against," White said. "I'll be gone. I think they're already going for me."

Lt. Col. Paul Forshey, who recently retired as the National Guard's top lawyer, or JAG officer, said he was dismayed that a list of reforms suggested by a panel of high-ranking officers was disregarded by top leaders. "I have never seen a board like that ... where command did not follow the recommendations of three senior officers."

The Guard last week accused Forshey of violating attorney-client privilege and threatened him with a state Bar complaint for speaking with The Republic, but he said he won't be silenced. He said an ethical breakdown has created a culture of arrogance.

"It's hubris," added Forshey, who reviewed disciplinary cases as part of his job. "They (wrongdoers) know nothing's going to happen. Nobody can touch them ... This is the inbred stepsister of the active-duty military."

White, who was among three officers who uncovered widespread misconduct in the Recruiting and Retention Command during 2009, said recommendations were mostly discarded and culpable soldiers received minimal discipline.

Salazar denied ignoring recommendations for reform. He said suggestions were carried out, though with modifications. He also rejected inferences of a problematic culture.

"We do not have a corrupt command climate in either the National Guard or in recruiting," he said. "We address misconduct. The criticism is neither fair nor true."

Asked what message he would offer to potential recruits and to family members who might have concerns, Salazar said: "Don't view the organization according to a couple of bad apples. I'm extremely proud of the AZNG, and we do some amazing things ... Military service will make you a better person regardless if you serve three or 30 years."

The Republic's inquiry focused on issues in the state's Army Guard. However, similar problems in the Air Guard, which also serves under Salazar, resulted in the dismissal of five top officers in recent years. As The Republic reported in September, commanders of the Guard's F-16 wing were fired in connection with harassment of a female fighter pilot, and leaders of the Predator surveillance group were fired after auditors uncovered what they alleged were fraudulent expense payments totaling $1.1 million.

Salazar relieved the Air Guard's commander, Brig. Gen. Michael Colangelo, after an Air Force inspector general report found Colangelo abused his authority and retaliated when he fired the subordinate officers. An Air Force spokeswoman, Capt. Candice Ismirle, said questions concerning Salazar's conduct were referred to the Secretary of the Army's inspector general.

Colangelo has denied allegations against him and, in letters of appeal, claimed he was ousted for trying to uphold the military code of conduct.

Salazar said any portrayal of the National Guard as being corrupt would be inaccurate and a disservice to thousands of honest and courageous personnel serving their state and country.

"We do not tolerate misconduct. We don't ignore complaints," he said. "There are a lot of people doing great things. I hate the fact that a few are going to tarnish the image of the organization, because the National Guard doesn't deserve that."

Questions of discipline

The Republic filed public-records requests and obtained more than a dozen military investigative files dating back to 2006, many of which show recommendations for reform and tough discipline. Yet, in interviews and sworn testimony, Guard officers say egregious offenders frequently face minimal consequences.

Non-commissioned officers caught driving drunk in military vehicles were given reprimands. Recruiters found to have forged enlistment records or taken fraudulent bonus pay received transfers. Sergeants who had affairs with teenage recruits were given counseling.

One NCO who allegedly got drunk with privates and had sex with a female enlistee was allowed to deploy overseas, where he was disciplined for inappropriate sexual relations with two more subordinates. Instead of being discharged from the military, records show, he transferred to the California National Guard as a recruiter.

Some who sought to uphold Army standards by reporting unethical behavior were shunned, harassed and threatened with demotions.

Records obtained by The Republic also describe how a former prison inmate allegedly was used to retaliate against one whistle-blower. Police records contain allegations that the ex-con, who now faces criminal harassment charges, issued a death threat, obtained stolen personnel records, made false criminal accusations and posted derogatory fliers near the National Guard headquarters.

Hostility and paranoia escalated to the point where, in violation of National Guard regulations, some NCOs in the Recruiting Command sneaked guns into their offices at a shopping mall out of fear of a violent reprisal, records show.

Corrupt conduct is described in numerous investigative reports by military officials. One completed in 2009 by Maj. Nathaniel Panka focused on fraud and improper relationships. It noted: "Several comments were made by an alarming number of NCOs in this (recruiting) command. The two most troubling were: 'It doesn't matter how much you investigate, nothing is going to happen ...' and 'I don't want to make a statement because, if I do, the first time I screw up and don't make mission, I'll be fired. There is a network of people that have dirt on each other here, and if you're not 'in' then you have to watch your back.'"

Panka wrote that soldiers gave similar answers when asked why they allowed wrongdoing to go unchecked: "Every single one of the NCOs we interviewed said, 'It will cost us our job if we bring this up.'"

Over and over during investigations in 2009-10, soldiers testified that high-level commanders in the National Guard were in no position to reprimand subordinates because some of them had fraternized with subordinates in violation of Army Command Policy which prohibits other-than-professional relationships between officers of differing ranks, officers and enlistees or soldiers and prospective recruits.

White said the Guard's full-time work force of about 2,700 employees is equivalent to a high school student population, except that most of the personnel have been together for more than a decade. The result: Friendships, promotion powers and mutually destructive information make it difficult to root out wrongs -- especially sexual misconduct.

"It's good ol' boys," White said. "It's like a college fraternity. It's not an Army organization. It's a frat house." Litany of offenses

Allegations of criminal or ethical violations are the subject of military reviews known as 15-6 investigations, command-directed inquiries and inspector general reports. Documentation typically includes detailed interviews, findings and recommendations.

Behavior at the Arizona National Guard documented in military records include:

"Bum hunts" -- Thirty to 35 times in 2007-08, Sgt. 1st Class Michael Amerson, a former "Recruiter of the Year," drove new cadets and prospective enlistees through Phoenix's Sunnyslope community in search of homeless people.

Military investigators were told that Amerson wore his National Guard uniform and drove a government vehicle marked with recruiting insignia as he and other soldiers -- some still minors -- shot transients with paintballs or got them to perform humiliating song-and-dance routines in return for money. During some of these so-called "bum hunts," female recruits said, they were ordered to flash their breasts at transients. Homeless women, conversely, were offered food, money or drinks for showing their breasts.

Amerson, during military interviews, denied paintball assaults but admitted to some wrongdoing. He was demoted to private and given an other-than-honorable discharge. Amerson declined to be interviewed for this story except to say that allegations against him were untrue.

Sexual misconduct -- Military investigative records describe multiple cases of sexual relations, abuse or harassment by male recruiters against female cadets and enlistees, as well as fraternization in violation of military regulations.

In a case last year, two investigators concluded independently that an NCO in the National Guard's Human Resources Office had retaliated against a female soldier after she rebuffed his alleged attempt to kiss her while at work.

According to military records, both investigators found that Chief Warrant Officer Jerardo "J.C." Carbajal was unfit to supervise any personnel, especially women. Earlier this year, Carbajal was assigned as the Army Guard's TAC officer (training, advising and counseling) for enlistees striving to become warrant officers. Salazar said Carbajal no longer has supervisory responsibilities.

Recruiting violation -- Investigators uncovered several schemes where recruiters collected unwarranted bonus pay.

Under a Pentagon program known by the acronym GRAP (Guard Recruiting Assistance Program), soldiers credited with enlisting others can collect awards of $2,000 each.

In 2008, Sgt. Cirra Turpin admitted $12,000 in bonuses for which she was not eligible. Although investigators recommended termination, 29 supervisors and colleagues wrote letters saying Turpin should not be so severely punished. She was reassigned as a military police officer.

During a 15-6 inquiry, officers asked the recruiting commander, Lt. Col. Keith Blodgett, to explain.

Question: "What if she had robbed a bank?"

Blodgett: "That would've been a crime..."

Question: "What's the difference?"

Blodgett: "Good question."

Military records contain no evidence that Turpin was referred for criminal prosecution. Blodgett testified that he notified the Defense Department's National Guard Bureau of the improprieties. "It sounded like they weren't very concerned about it at all, which to me, indicated that that was something that was common," he said.

In an interview with The Republic, Blodgett said Turpin expressed remorse, paid back the money and had an otherwise clean record.

Today, GRAP fraud is the subject of a nationwide probe by the Department of Defense. According to a March report in the Washington Post, more than 1,700 recruiters are suspected of engaging in fraud. Salazar said fewer than 10 Arizona Guard recruiters are under suspicion, and he believes one will be referred for a full criminal investigation.

Meanwhile, Turpin allegedly used a Department of the Army stamp to falsify military documents and wound up getting discharged, according to National Guard records.

Turpin could not be reached for comment. She now is founder and owner of a Phoenix non-profit group known as Cirra's Cloud, which says it raises money for financially distressed families of deployed soldiers.

Forgeries -- Investigators also found that recruiters falsified academic documents, medical files and fitness tests to make potential enlistees eligible for service, or to qualify for promotions.

One Tucson recruiter forged the signatures of commanders on numerous documents and lied about it when first confronted, according to investigative records. He received a reprimand as discipline.

Blodgett was asked by an investigator, "Do you think that set a new standard inside the organization -- that forgery and lying equals keep your job?" Blodgett's answer: "When you put it like that, perhaps."

Drunken driving -- Several National Guard recruiters cited for DUI in military vehicles were either sanctioned lightly or faced no discipline.

One example: In October 2010, a top recruiter in Tucson was arrested on suspicion of DUI with other Guard members in his government vehicle. Military records indicate it was a repeat offense. The NCO initially was given a letter of reprimand, which was withdrawn and replaced with a less severe letter of concern.

Blodgett told investigators he requested an Article 15 proceeding -- a formal, non-judicial disciplinary procedure in the military -- which might result in discharge or severe punishment, but was overruled by the Guard's chief of staff. Records show that, after the recruiter was convicted and sentenced to jail, he was transferred to a transportation unit and demoted to staff sergeant.

The outcome seemed fair, Blodgett said, because higher-ranking soldiers also had been arrested for driving while intoxicated and were not fired.

Dishonesty -- In many of the documented cases of misconduct reviewed by The Republic, soldiers lied to investigators. Dishonest National Guard personnel in those investigations typically kept their jobs.

By comparison, outright dishonesty at civilian jobs often results in termination, said Steven Mintz, a professor and ethics specialist at California Polytechnic University. "Lying or covering up is always worse than the crime itself because it raises issues of trust and reliability."

Mintz said workplace discipline depends on employment contracts or conduct codes. However, in reference to the Guard issues, he added, "In private industry, those things would be firing offenses."

Salazar said it is misleading to compare civilian disciplinary standards with the Guard's. He said most non-military jobs are "at-will," which means a person can be fired without cause. By contrast, soldiers have extensive due-process and appeal rights under Arizona law and military regulations.

The goal of most Guard discipline, Salazar said, is not to punish or set an example, but to rehabilitate the offender. 'Numbers, numbers'

Recruiting and Retention Commands are unique in the military structure.

Often based in strip malls, recruiters deal directly with the civilian community, visiting high schools and family homes. They work without direct supervision and face pressure to meet enlistment quotas of two or three recruits per month -- especially in a post-9/11 military with no draft.

In over a dozen interviews, officers told The Republic the conditions produce an environment in which military regulations and ethical standards are eclipsed by a "mission-first" mentality. As one soldier put it, "We need to up the numbers. We want people in boots."

Enlisting new soldiers is a tough job. Those who succeed are lionized and rewarded. Many fail and are dismissed from full-time jobs in the Army Reserve Guard, becoming weekend warriors.

The high turnover makes recruiting nearly the only easy gateway into full-time employment with the National Guard. And it means commanders, who are measured by recruitment statistics, are hesitant to get rid of top performers.

During one investigation, Master Sgt. Keith Stall described how an NCO arrested for drunken driving got the proverbial slap on the wrist because he'd been named a top recruiter. "They looked at production, you know, how well you've done," said Stall. "Production, production, production. Numbers, numbers, numbers."

Sgt. Maj. Donald Wilcox Jr., with 27 years of military service, told investigators the recruitment mission trumped other values, with this message emanating from the Pentagon's National Guard Bureau: "If you drink our Kool-Aid, then we'll take care of you."

"I've gone to recruiting conferences where they had Michael Jordan as the speaker, Kid Rock, ice sculptures, crazy trips to spring break," Wilcox added. "Setting up, to me, an atmosphere of, 'Hey, if you're a recruiter, you're a rock star.'" Accountability questions

In late 2008, Lt. Col. White and two other officers conducted an investigation of leadership in the Recruiting Command.

They found numerous NCOs were dishonest and complicit in corruption. They found that Blodgett, the former recruiting chief, had failed to uncover gross wrongdoing or to take appropriate action when it was exposed.

Salazar, the adjutant general, initially reprimanded Blodgett for dereliction and "inexcusable" leadership failures, blocking promotion. But Salazar months later removed the letter to a restricted file, enabling Blodgett to this year win a coveted appointment to the Army Senior Service College, where he is virtually assured advancement to full colonel.

"How can this be?" White asked. "He failed as a commander. How is this in keeping with Army values?"

Salazar said under military regulations a reprimand is meant to rehabilitate, not punish. He said Blodgett did not engage in misconduct but failed to detect an outlaw culture. That merited corrective action, Salazar said, but not a permanent black mark for an officer with an otherwise clean record.

"A lot of this is subjective," Salazar added. "And I get second-guessed a lot ... (But) Col. Blodgett is a good officer. He works hard. He's conscientious. And since he was taken out of Recruiting Command, he has performed above and beyond."

Records show Blodgett argued he did the best he could after inheriting a recruiting operation where soldiers had no concept of Army standards. "I was aware of a pattern of unethical and illegal conduct going back at least two commanders and took aggressive action to eliminate this pattern," he wrote in protest of the reprimand. "My efforts to instill discipline and ethical standards were consistently impeded when my disciplinary action requests were downgraded, delayed or not acted on."

Blodgett told The Republic that much misconduct escaped his attention because of derelict subordinates. "I should have asked more questions," he added. "You trust, but verify. I should have verified more."

Like Salazar, Blodgett said recruiting oversight has improved.

But White and other officers said they've lost faith, especially when it comes to protecting female service members from harassment and sexual abuse. They said leadership is compromised, the Defense Department's inspector general is a "toothless tiger," and complaints to the Arizona Governor's Office are punted back to Maj. Gen. Salazar.

"As a female, you don't have any outlet," said one NCO who reported sexual harassment and retaliation. She asked not to be identified for fear of further reprisal. "Nowhere to go ... They don't want to be accountable. I don't think they want to do a damned thing."

Reach the reporter at dennis.wagner@arizonarepublic.com.

History of Arizona National Guard scandals

SourceHistory of Arizona National Guard scandals

by Dennis Wagner - Oct. 13, 2012 11:45 PM

The Republic | azcentral.com

The Arizona National Guard's newly disclosed problems are an extension of a troubled history.

Previous scandals include:

A 2005 FBI probe, Operation Lively Green, unveiled a southern Arizona narcotics smuggling ring of military personnel, prison guards and others. During a sting operation, Arizona soldiers working for a supposed Mexican cartel drove an Army National Guard Humvee to a clandestine airstrip, loaded 60 fake kilograms of cocaine and drove to a Las Vegas hotel to rendezvous with a federal operative posing as a buyer.

The FBI's case evolved from an initial tip about enlistment fraud in the Army National Guard. Ultimately, 57 suspects were convicted, including about a dozen soldiers and airmen. Some convicted personnel were allowed to resign with honorable discharges.

In 2006, Col. Donald Wodash Jr., then the Arizona Guard's deputy chief of staff, went on a military training trip to Arkansas. According to court records, Wodash contacted a 14-year-old girl on his Army computer, used a webcam to display his genitals, then arranged a rendezvous.

It turned out the "girl" was a police undercover detective. Wodash was sentenced to four years in prison, but was not fired. Instead, the colonel was allowed to collect his paycheck while awaiting trial.

Wodash eventually was reprimanded for misuse of a government computer, but with a notation that "this letter is not imposed as punishment." He was discharged "under honorable conditions" and retired with his pension.

Maj. Gen. Hugo Salazar, the current National Guard commander, said a predecessor, Adjutant General David Rataczak, acted out of compassion: "He just felt why should he punish the family -- the spouse?"

National Guard Chaplain Kurt Alan Bishop was convicted in 2010 for falsely adding a Bronze Star, Purple Heart and other prestigious awards to his military record over two decades. Bishop, who profited because the false honors led to increased pay, received an other-than-honorable discharge, pleaded guilty in federal court and was sentenced to probation.

More recently, a Guard emergency fund for financially struggling families of deployed soldiers was nearly wiped out. In February, retired Col. James E. Burnes pleaded guilty to embezzling $2 million as resource manager for the Arizona Department of Emergency and Military Affairs, an umbrella agency over the Arizona Guard. The admitted gambler drew a 3.5-year prison sentence.

Officer serves in Arizona National Guard despite complaints

SourceOfficer serves in Arizona National Guard despite complaints

by Dennis Wagner - Oct. 13, 2012 11:45 PM

The Republic | azcentral.com

Two military investigators last year concluded that the Arizona National Guard should never place Chief Warrant Officer Jerardo "J.C." Carbajal in a position of authority over women. Yet, months later, he was assigned to a unit that trains prospective warrant officers.

Carbajal's appointment to the training unit is one among many decisions listed by critics who say the Arizona National Guard has repeatedly failed to protect female soldiers and airmen from sexual misconduct.

Investigative files obtained by The Arizona Republic show Carbajal was accused of sexual harassment and retaliation after an August 2011 incident involving Staff Sgt. Carrie Armstrong, a non-commissioned officer in the National Guard Human Resources Office.

Armstrong told investigators that Carbajal approached her from behind in a stairwell and attempted to kiss her while saying, "I want you." Armstrong said she pulled away, and there were no immediate repercussions. But after the rebuff, she alleged, Carbajal and other soldiers launched a campaign of harassment that escalated once a formal complaint was filed.

Armstrong complained that co-workers spread rumors questioning her mental health and fabricated accusations against her that led to probation, a blocked promotion and outcast status.

In one e-mail to a commander, Armstrong wrote: "I am subjected to dirty looks, snide comments and rudeness throughout the day. The most appalling part of all this is that this atrocious behavior is being done by officers in this state, and I feel as though senior leaders are standing by, not only watching it happen, but allowing it."

A formal military probe of Armstrong's complaint, known as a 15-6, was ordered in November 2011.

The investigator, Lt. Col. Laurence Bishop, obtained statements from other soldiers and reviewed e-mails and phone records.

Carbajal supporters described him as an excellent warrant officer and portrayed Armstrong as a troublemaker. But other female soldiers told of being stalked or intimately involved with Carbajal.

Carbajal declined interview requests, but emphasized in an e-mail that the accusation that he attempted to kiss Armstrong was not substantiated.

Armstrong declined comment for this story.

As the inquiry into Armstrong's allegations proceeded, Bishop uncovered additional allegations of misconduct and advised commanders that "a more sweeping investigation (should) be done into possible inappropriate behavior/fraternization ... I am up to 13 people who (may) have involvement due to the intermingling of relationships."

Bishop eventually concluded that, without witnesses, the attempted kiss was unproven but credible because of Carbajal's "clearly established pattern of making advances on females in uniform."

He described Carbajal as "a manipulative womanizer, unafraid to pursue anyone regardless of their position or rank ... guilty of conduct unbecoming an officer and insubordination, at the least. He ... is not suitable to be an officer and leader of the Arizona Army National Guard."

Bishop determined that the evidence proved Armstrong was a victim of retaliation.

In the 15-6 report completed last December, Col. Ellen Reilly, the human resources commander, described the National Guard as infested with improper relationships, cronyism and dishonesty.

"All in all, my impression is that there are layers and layers of misconduct, fraternization and manipulation that have been going on for some time in this organization," she said. "I believe there needs to be a swift and decisive punishment to make a statement."

Bishop recommended that Carbajal be removed from his paid position in the Army Reserve Guard, writing: "His continued presence undermines good order and discipline while providing exactly the wrong role model for junior officers and NCOs to emulate. His disdain for authority and contempt for others further reinforce that he is incompatible with military service. This officer personifies all that give the National Guard (and indeed the military) a bad reputation."

But Carbajal had served 18 years in the military, and was protected from firing by a regulation known as "sanctuary," which insulates soldiers from termination as they near retirement. "If there is no way to remove him due to sanctuary," Bishop noted in his report, "then strip CW3 Carbajal of any position of authority and influence."

An Equal Employment Opportunity investigator issued similar recommendations after completing a parallel inquiry, also in December. No matter what, she wrote, Carbajal "should not be in a supervisory or leadership role, and should not supervise females in any capacity."

Maj. Gen. Hugo Salazar, the Arizona National Guard commander, said Carbajal was reprimanded, given a non-judicial punishment known as an Article 15, and notified that his services are no longer needed.

It is not clear what happened after that. But Carbajal remains in the National Guard. Salazar recently confirmed that Carbajal was assigned as the training, advising and counseling (TAC) leader for soldiers striving to become warrant officers.

Lt. Col. Rob White and other officers critical of National Guard disciplinary practices said Carbajal initially was placed directly over trainees and in contact with new recruits.

"To put him back there is, to me, outrageous. It scares me," said White. "That is the epitome of what's wrong with this organization."

Salazar said Carbajal has a desk job and does not directly supervise trainees. In an e-mail, Carbajal confirmed that his duty is confined to scheduling, logistics and paperwork.

Sexual misconduct has been a problem for the military nationwide.

In May, after the Pentagon reported 6,350 sexual-assault cases over a two-year period, chiefs of all U.S. services issued a memo ordering commanders to prevent and combat abuse, saying: "Sexual assaults endanger our own, violate our professional culture and core values, erode readiness and team cohesion and violate the sacred trust and faith of those who serve and whom we serve."

Misconduct doesn't define Arizona Guard

SourceMisconduct doesn't define Arizona Guard

by Hugo E. Salazar - Oct. 7, 2012 06:44 PM

I am proud of the brave men and women who serve in the Arizona National Guard on American soil and around the world. Our brave soldiers and airmen embody our motto: "Always ready ... always there."

I could fill this page with the awards and combat-service medals earned by our Arizona National Guard personnel, including several who've received national recognition for their individual achievement. Taken together, the exemplary efforts of our servicemen and women are what make it possible for the Arizona National Guard to be, in my opinion, one of the nation's best.

I say all of this not because I believe the Arizona National Guard is perfect. It's not. Recently, The Arizona Republic has chosen to highlight the misconduct of a small number of officers who've been removed from leadership posts at the Arizona National Guard, including a brigadier general who believes he was wrongly terminated. I expect Republic readers will see similar stories in the days ahead, in some cases detailing service-member incidents and misbehavior that dates back several years.

Organizations are composed of human beings, and human beings have faults. As the leader of this organization, all I can do is pledge that the Arizona National Guard will act swiftly, fairly and appropriately to address all allegations of misconduct. That's exactly what I've done since becoming adjutant general of the Arizona National Guard in December 2008. Every misconduct allegation brought to my attention has been fully investigated and adjudicated, with service members held accountable for their actions.

For example, in early 2009, my command staff and I discovered misconduct among some of our recruiters. The allegations and incidents varied from misuse of a government vehicle to inappropriate relationships with trainees and fraud. Making matters worse, there was evidence the individuals in question attempted to cover up their activities and suppress or intimidate military witnesses.

In the most egregious case, the recruiter -- a senior, non-commissioned officer -- was reduced to the lowest military rank (E1), removed from military service with an other-than-honorable discharge and forced to forfeit all military benefits. A handful of other individuals implicated in lesser recruiting misconduct received discipline ranging from reduction in rank to loss of full-time status.

To help prevent this kind of situation from happening again, I allocated additional management resources and reorganized recruiting to report directly to the assistant adjutant general. Additionally, I developed an action plan that includes development of an agencywide ethics program.

I won't make excuses for misconduct, nor will I tolerate it. But it would be a gross injustice if the mistakes of a few individuals were used to impugn the character and service of the entire Arizona National Guard.

The Arizona National Guard takes all allegations of misconduct seriously. I hold our servicemen and women to the highest standard. Nine times out of 10, they meet or exceed that standard. When they fall short, we have investigations -- with findings based on fact, not rumors, speculation or the sort of idle gossip trafficked in by disgruntled current or former service members.

I only wish newspapers would meet the same standard.

Maj. Gen. Hugo E. Salazar is the adjutant general of the Arizona National Guard.

Whistle-blower who exposed National Guard misconduct had 'target on his back'

More on Arizona National Guard corruptionWhistle-blower who exposed National Guard misconduct had 'target on his back'

by Dennis Wagner - Oct. 14, 2012 11:06 PM

The Republic | azcentral.com

On the morning of May 28, 2009, Staff Sgt. Chad Wille, a recruiter for the Arizona Army National Guard, was confronted at a Phoenix gas station by an angry bicyclist.

The bicyclist pointed to the soldier's military Humvee with distinctive camouflage paint, noted its license plate and said he'd seen that same vehicle drive down Seventh Street six weeks earlier while its occupants shot pedestrians with paintballs.

Wille, who had been away at recruiting school during that period, returned to his office in Sunnyslope and reported the allegation to 1st Sgt. Lucas Atwood, his supervisor in the Recruiting and Retention Command.

Wille also questioned Master Sgt. Joseph Martin, a colleague in the recruiting unit who had custody of the Humvee keys at the time of the alleged paintball attacks. According to military records, Martin said he had given the keys to another recruiter, Sgt. 1st Class Michael Amerson, then asked Wille, "You're not aware of the bum hunts?"

Over the next year, Arizona National Guard commanders would learn about clusters of alleged criminal and unethical behavior by Guard members that included patrols through north Phoenix to assault and humiliate homeless people. Witnesses alleged Amerson and other soldiers were involved in sexual misconduct, recruiting improprieties and cover-ups. Military investigators ultimately substantiated allegations, concluding that the recruiting office was infected with corruption because of command leadership failures.

But as the investigations progressed, Wille became a target, military and police records show. Instead of being rewarded for integrity, he was subjected to a two-year campaign of harassment. Records show he was falsely accused of groping a teenage girl and threatened with a bullet to the head. His confidential military records were provided to an ex-convict. His National Guard photograph was stolen and posted on derogatory fliers outside National Guard headquarters, known as the Papago Military Reservation, in Phoenix. He was subjected to other allegations, investigated and pressured to resign, but refused.

Pandora's box

This story, drawn from interviews, police records, court files and thousands of pages of military investigations, begins with the "bum hunts."

Wille, a former Indiana reserve police officer, told military investigators that the bicyclist's allegations, if true, amounted to criminal assault, misuse of a government vehicle and other offenses.

Atwood told him that Amerson denied knowledge of paintball attacks. No other soldiers talked. The issue was closed. Atwood told Wille, "Just let it go."

Wille insisted on filing a written report. Within hours, he began getting calls from fellow officers. They demanded to know if he was a team player, then warned him to back off. According to National Guard case files, Amerson sent Wille a taunting text: "Ha, ha, ha ... First Sgt. Atwood ain't going to do anything."

Wille later told investigators he was outraged by pressure tactics and challenges to his integrity. "I got a little angry, and the police department (training) came back out of me," he noted.

Wille started talking with young enlistees. Within hours, a 17-year-old private admitted taking part in missions targeting the homeless. (A recruit may sign up at age 17, the minimum age, with a parent's signature.) The teenager said she and other female cadets were pressured by Amerson to cruise with him and flash their breasts at indigents, who were induced to dance, sing or show their own bosoms for money.

In one case, the private said, Amerson offered a homeless woman $10 to expose her breasts, refused to pay, then screeched away as the lady grabbed onto the recruiting vehicle's passenger window. "The female was pulled along and then spun off the car, landing on the ground," notes an investigative report. "She (the soldier) did not know if the female was hurt because they did not stop."

Wille took the cadet to a supervisor, where the allegations were repeated. More soldiers were interrogated. Some received phone calls from colleagues as they were being interviewed, warning them to lie or remain silent, according to military records.

But the Pandora's box had opened. Witnesses eventually testified that Amerson, while in uniform, led 30 to 35 nighttime raids through north Phoenix to harass homeless people. At least a dozen Guard members and recruits took part, while others looked away.

Confessions led to more disclosures of wrongdoing, more investigations. One private, who was enlisted by Amerson and joined in the escapades, told investigators: "I wasn't following the Army Code of Conduct -- the rules of the Army -- and I guess I sort of got that idea from Sgt. Amerson that 'You can do whatever you want, as long as people don't know.' "

Reached by phone, Amerson declined to be interviewed. "There was nothing behind any of that," he said before hanging up.

'Bum hunts'

Military witnesses later testified that Amerson, a top recruiter, was known for bragging and exaggerating.

Lt. Col. Keith Blodgett, then commander of Army Guard recruiting operations, told a panel of officers Amerson was "a big muscular guy, kind of like Johnny Bravo, you know, that cartoon character."

Even Atwood, Amerson's supervisor and friend, testified that the sergeant was "one hell of a bulls--tter," adding, "That's why he was a good recruiter."

All testified they had heard Amerson describe bum-hunting expeditions, but claimed to believe the tales were fabricated. Martin, a supervising officer, heard the stories so many times he was able to recite a detailed anecdote about the abduction of a homeless man.

"Supposedly he was like a Vietnam veteran or something, and that's why they named him 'Checkpoint Charlie,' " Martin told investigators. "So they buy coffee and Checkpoint skips out on the tab, so now they're pissed at him. So the story goes, 'Hey, we're going to take you out in the desert, dump you out in the desert.' Maybe to scare him. I don't know.

"Checkpoint had his cell phone and was going to call the police. So Amerson swung around the back seat, grabbed his cell phone, was going to smash it. Then they get back to wherever it is that they picked up this Charlie guy at, and they're all standing around and Checkpoint has like a railroad tie (spike) or something and grabs (another soldier) puts him in a headlock and says, 'I'm going to kill you.' I guess somehow Amerson diffused the situation or something to that affect (sic)."

Martin told investigators that he never believed the stories -- even after Wille began asking questions. When Amerson was suspended after young soldiers confirmed the bum hunts were real, Martin testified, he and other recruiters became so fearful of retaliation that they brought guns to their office in a Phoenix mall, violating Guard regulations.

"He (Amerson) had his own guns," Martin explained. "I started wearing my pistol to work, kept it in my backpack."

Chicken fights

Fraternization offered yet another sign that some in recruiting command were out of control.

Military command policies prohibit fraternization, or non-official relations, between National Guard officers and subordinates or prospective enlistees.

In January 2007, Blodgett, who oversaw recruiting, published a command philosophy that warned of danger areas. "Do the right thing," Blodgett wrote. "Be self-policing and hold each other accountable when you see your brother or sister slipping. Guard your integrity jealously."

Yet, according to National Guard records, Amerson avoided discipline throughout a years-long series of improper relationships with recruiting prospects and cadets.

During military inquiries known as 15-6 investigations, soldiers told military investigators that Amerson held pool parties where potential enlistees and new soldiers -- male and female -- were served alcohol and engaged in topless "chicken fights." One recruit, only weeks in the National Guard, wrote a letter to the commander giving notice that she was quitting because Amerson pressured her to take part in bikini parties.

A teenager in training claimed Amerson took her into his private office alone and instructed her to remove her shirt so he could determine whether she was pregnant. According to investigative records, she wept describing how he used a tape measure and fondled her, making her feel "dirty and disgusted," then took her to a pharmacy to get a pregnancy test, which came out negative.

Amerson acknowledged to investigators that another prospective recruit moved into his home as a minor, according to his 15-6 interview. The relationship was exposed when the teen was accused of stealing a credit card from the residence. Amerson received no formal punishment. The female, by then a new soldier, was ostracized and subsequently agreed to be discharged.

Finally, witnesses told of another recruit who became Amerson's third wife. Sgt. Atwood denied being derelict in oversight but acknowledged serving as best man at the wedding. Atwood told investigators he had counseled Amerson repeatedly for conduct issues, but never imposed or recommended formal discipline because his bosses did not instruct him to do so.

Atwood declined comment for this story.

Sgt. 1st Class Marie Ann Neilson told investigators she reported an Amerson affair with a teenager, but supervisors reacted by forcing the female soldier to quit the National Guard. "Everybody was yelling at her for an inappropriate relationship," Neilson told them. "But he (Amerson) was the guy: 'Hey, good for you. You got the young girl.' And that was their attitude.

"This is a very young, naive girl ... You look at her and think she's a high-school cheerleader, the president of the glee club. Her career is over and nobody cares because Amerson was a superstar at the time. It was just washed under the rug."

Trumped-up charge

Within days after exposing corrupt conduct and lax supervision in recruiting operations, Wille was rebuked for breaching the chain of command. He also was given a reprimand because he had fallen one enlistment shy of his recruiting quota.

Still, the wheels of military justice churned with inquiries. Soldiers were punished for misconduct. Some non-commissioned officers were reprimanded or demoted.

Wille became a pariah. At one point, he told an investigative panel he was shunned for trying to do the right thing. "Now I'm the narc," he said. "Now I'm the one going wrong."

On June 25, 2010, a man named Don Lee Scott called the recruiting command and requested a meeting to discuss soldier misconduct. At a coffee shop near National Guard headquarters, Scott told Master Sgt. Daniel Cardiel that a 16-year-old girl had met a recruiter weeks earlier while stopped at a traffic light. He claimed the National Guard officer got the girl's phone number and arranged a rendezvous on a later date, where he touched her breast. The officer Scott accused: Chad Wille.

According to military files and Phoenix police records, Scott gave Cardiel handwritten pages containing Wille's Social Security number and Army records that could only have been obtained from confidential military files. In a written statement, Scott said discipline of Wille should be "nothing less than discharge from the Arizona National Guard."

Cardiel reported the accusation to his supervisors. An inquiry was assigned to Capt. Reinaldo Rios.

Wille told Rios he didn't know Don Scott, had never met the alleged victim, and didn't know what was going on.

Scott did not make the girl available for an interview, and declined to tell how he obtained military records protected under federal privacy laws. Rios reported to his supervisor that the story was suspect: Scott had not filed a police report about the alleged fondling, and provided no evidence for it.

Rios concluded that Wille was being set up. National Guard records show Rios then became the subject of an investigation, and received a reprimand, because he provided information to Wille about Scott.

Maj. Benjamin Luoma was assigned to a deeper probe of Scott's accusation. Once again, Scott failed to cooperate. Luoma found "no credible evidence" of sexual abuse by Wille.

While that inquiry was under way, three other recruiters filed unrelated complaints against Wille, claiming he violated recruiting protocols, made inappropriate comments and misused a government vehicle.

On July 1, 2010, Wille was ordered to meet with superior officers, including the recruiting commander. Upon arrival, Wille said he was pressured to quit the National Guard and handed a pretyped resignation letter. Wille refused to sign, left the meeting, and returned later with his own letter alleging that he was a victim of retaliation.

A parallel investigation was by then under way to determine how a civilian had obtained Wille's confidential military records, a breach so serious that the Arizona National Guard was locked out of the Pentagon's personnel system for a week.

Scott, who claimed to be a former U.S. Marine, told investigators Wille's personnel information was given to him by someone "back East." When pressed for details, Scott announced he wanted the entire probe dropped.

The military investigator recommended a full inquiry by the Department of Defense. He also concluded that Wille "was likely the target of a personal grudge."

Death threat

On Oct. 1, 2010, Wille received an anonymous call at work. He put his cellphone on speaker mode so other soldiers could listen. According to a Phoenix police report, the caller warned that at an unexpected moment he would "walk up behind (Wille) and put a .45 against his head and blow his brains out."

Soldiers who heard the conversation were later given a recording of Don Scott's voice and filed sworn statements declaring that it sounded the same as the threat call.

Scott denied responsibility when police contacted him.

A month later, someone taped fliers in public places outside National Guard headquarters on McDowell Road. The posters featured Wille's military photograph with disparaging information, including a warning that the sergeant was "a professional tattle-teller."

Wille delivered them as evidence to Phoenix police, asking for fingerprint tests. The National Guard verified that the photo was stolen from Wille's personnel file, though investigators could not identify the thief.

Wille sought an anti-harassment order against Scott in Phoenix Municipal Court. A hearing was held Dec. 8, 2010. According to a police report, as Wille exited the court afterward, he overheard Scott on a cellphone speaking with Brig. Gen. Alberto Gonzalez, the National Guard's chief of staff.

Phoenix police Officer Jonathan Alberta visited Gonzalez, who confirmed that he spoke with Scott but said the call was not about Wille. Rather, Gonzalez said, Scott called to complain that Capt. Rios, who first investigated the groping allegation, testified in court on behalf of Wille. Gonzalez told Alberta that he and Maj. Gen. Hugo Salazar, the top officer in the Arizona National Guard, "had told Don he could call them anytime with any concerns he may have."

Salazar said he was dealing with a civilian who had lodged a serious complaint against a soldier, and sought to be open and transparent.

Amid the turmoil, Capt. Scott Blaney, the National Guard's deputy judge advocate general, or JAG, was assigned to investigate Wille's retaliation complaint. Blaney found "no evidence that the AZNG or any of its members have taken an unfavorable personnel action" against Wille.

Blaney also rejected Wille's complaint that someone in the National Guard stole his personnel records. Instead, the captain suggested, Wille may have been "a little careless in safeguarding his own personnel documents."

Fingerprints and calls

On Jan. 20, 2011, Phoenix police-lab testing of adhesive tape used on disparaging posters contained a print "identified to the right middle finger of Donald Lee Scott."

According to the police report, Scott suggested that Wille must have "gone to his house, gone through his recycling bin, found an aluminum can, lifted a fingerprint ... and placed it on a flyer in order to frame him." Scott also denied knowing any recruiting officers in the National Guard.

The police probe escalated. Officer Alberta joined forces with Juan Concha of the Defense Criminal Investigative Service, who was trying to learn who stole Wille's personnel records.

Several NCOs in the Recruiting Command were ordered to appear for questioning at the JAG office. They were told that they were not suspects and, for reasons that remain unclear, they were not given Miranda warnings. All of them, including Sgt. 1st Class Joseph Martin, denied knowing Don Scott.

Wille, meanwhile, had submitted a public-records request for National Guard cellphone records. In February 2011, he received a list of eight recruiting officers whose phone records showed repeated contacts with Don Scott, some before Wille was accused of sexual misconduct. According to police, a phone assigned to Sgt. Martin was linked to 173 calls to Scott's phone.

Alberta wrote that Martin "lied" about not knowing Scott. He concluded that "members within the Army National Guard conspired with Don Scott to have Chad Wille demoted or removed."

Martin could not be reached for comment, and his attorney declined to be interviewed.

Scott was charged in March 2011 with misdemeanor use of a telephone to terrify and with harassment. The case is pending.

Court files include a rambling, 16-page memo by Scott that accuses Wille of harassment. In September, Scott was ordered to undergo a mental-health screening. A court hearing is scheduled for Thursday.

According to court records, Scott has criminal convictions for harassment, endangerment and aggravated assault dating to 1987. Arizona Department of Corrections records show a 1999 conviction for harassment and a yearlong term in prison for probation violations.

In a recent interview with The Republic, Scott said he suffered a head injury in March and lost all memory of the past five years.

Nevertheless, he discussed the National Guard controversy in detail, claiming he based his knowledge on written notes and official records.

He admitted being friends with recruiting command officers before he accused Wille of sexual abuse. He acknowledged receiving personnel files from a National Guard officer. But he claimed to be a victim of harassment, not a perpetrator.

Epilogue

Numerous recruiters tied to Sgt. Wille's case have been demoted or reprimanded. Among them, according to military records and Maj. Gen. Salazar:

Investigators found Amerson culpable for fraternization, vehicle misuse, recruiting improprieties and dishonesty. He was demoted to private and given an other-than-honorable discharge. He was not criminally prosecuted or court-martialed. His discharge evaluation says: "Failed every soldier, NCO and officer in the command by using his position for his own pleasure and personal gain."

Atwood was found to be derelict, demoted and discharged from the National Guard.

Martin is the only soldier to face court-martial. He was charged with being an accessory to Scott's harassment campaign, making false statements and general misconduct. Salazar said he believes it was the first court-martial case in Arizona Guard history. "I wanted to go after him. I wanted to send that signal," he said.

In April, charges against Martin were dismissed after a military judge suppressed Martin's statements because investigators failed to read him his Miranda rights.

Salazar said Martin was near retirement age at the time, and therefore in a protected status known as "sanctuary." Under military regulations, firing him would have required approval from the Secretary of the Army. So Martin was reduced in rank for misuse of a government cellphone. He was placed on leave, then retired with benefits.

Wille said in an interview earlier this month he feels betrayed by National Guard colleagues and leadership.

He said he was forced to conduct investigations in his defense for two years. He said he filed complaints with the Defense Department's inspector general, but got no response.

He said a staffer with Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., set up an interview at the Governor's Office that was later canceled because, he was told, Maj. Gen. Salazar was dealing with the matter.

"They don't try to do the right thing," Wille said of the Guard. "They're too busy looking out for the agency and trying to cover up."

Salazar said each allegation and complaint by Wille was investigated, and National Guard leaders tried to accommodate his needs under the stress.

"To allege that this organization reprised against anyone, to include Sgt. Wille, is unfounded," Salazar added. "I am not saying Wille didn't have a target on his back. Somebody was out to get him ... (But) we made every effort to try to protect him ... To be honest, Wille just never felt that we did enough."

Salazar said he recently updated the National Guard's whistle-blower policy and ordered training to clarify prohibitions against reprisal.

Reach the reporter at dennis.wagner@arizonarepublic.com.

Arizona Army National Guard recruit says sergeant sought to hide fraternization

Source

Arizona Army National Guard recruit says sergeant sought to hide fraternization

by Dennis Wagner - Oct. 14, 2012 11:47 PM

The Republic | azcentral.com

In early 2007, Staff Sgt. Lloyd Stenglein began recruiting a high-school girl from Scottsdale. Twenty days later, the teenager enlisted in the Arizona Army National Guard.

The cadet later told investigators, their friendship included going out to movies, meals and, on one occasion, to a strip club.

Personal relations between recruiters and cadets are expressly banned under Army Command Policy 600-20.

Around midnight on March 2, 2007, the teen was riding on the back of Stenglein's motorcycle when it crashed. She suffered double-compound leg fractures.

According to military investigative records, the accident was concealed from the National Guard even though the teen repeatedly missed required training exercises. Ten months later, while being disciplined because she still could not handle physical drills, the cadet blurted out her story.

Stenglein declined comment for this story.

An investigation of alleged fraternization, known as a 15-6, was conducted by Capt. Scott Lay.

Stenglein told Lay his relationship with the recruit was purely professional and did not involve movies. The night of the crash, he said, she called him from a party asking for a ride, so he agreed to help.

The recruit's hand-scrawled account in an investigative file differs dramatically. She wrote that she and Stenglein had exchanged calls that day about seeing a film, and wound up going to "Ghost Rider," about a stunt motorcyclist who sold his soul to the devil.

On the way home, she wrote, Stenglein wore the helmet as the bike hit speeds of 120 mph on a freeway. "Down my street to my grandma's house there are speed bumps. I just remember him saying, 'Hold on,' and he did a wheelie and gassed it. The next thing I remember was picking myself off the ground."

Besides a broken leg, the cadet suffered a head injury, bruises and road rash. Her written statement says Stenglein "freaked" as she lay bloody on the ground. "He said, 'What if I were to leave you here and you can call the cops and say someone ran you over?' I shouted at him, saying he's not going to leave me there."

No ambulance was called. Stenglein took her to a Scottsdale hospital, where she underwent surgery.

The recruit said Stenglein convinced her to claim that her foot had slipped off the motorcycle peg, and to provide a false story for an insurance-claims agent. She alleged he also persuaded her to go along with plans to accept military pay while concealing her absence from weekend duty until her leg healed.

Lay, the Guard investigator, checked phone records and found that Stenglein and the recruit had exchanged 362 calls, 13 of them on the day of the accident. He concluded that Stenglein was untruthful in sworn statements, had an "inappropriate" relationship and falsified pay documents for the cadet.

Lay recommended Stenglein's ouster from officer-candidate school, where he was enrolled at the time. He urged commanders to consider removing Stenglein from his paid position in the Army Reserve Guard, and to convene a court-martial or discharge board.

Stenglein was given notice of separation from the military -- effectively, a termination -- in 2008. Records provided to The Arizona Republic do not clarify what happened. But today, Sgt. 1st Class Stenglein leads the Guard's Ultimate Fitness Challenge.

During the 15-6 investigation, Stenglein denied the cadet's account and invoked his right to not answer questions.

After concealing her accident and her role in the subsequent cover-up, military records say, the cadet had a second improper relationship with a recruiting sergeant, which she lied about. Still, Lay concluded that she remained "trainable," and should face only an administrative reduction and undergo mentoring. Her status today could not be ascertained. The second recruiter, found guilty of fraternization and false statements, was recommended for other-than-honorable discharge. Available records do not indicate his status.

Lay also determined there was a failure of leadership in the Recruiting and Retention Command. He recommended additional training in ethics and leadership.

Arizona National Guard reform hard even with Brewer's support

SourceExperts: Arizona National Guard reform hard even with Brewer's support

by Dennis Wagner - Oct. 15, 2012 11:39 PM

The Republic | azcentral.com

Gov. Jan Brewer's decision to launch an independent evaluation of the Arizona National Guard represents a first step in reform efforts advocated by insiders and experts on military conduct.

The governor's call for a review of the Guard comes in response to an Arizona Republic report detailing allegations of sexual abuse, recruiting improprieties, forgery, whistle-blower retaliation and other misconduct in a Guard with about 9,000 personnel, including 2,300 full-time soldiers and airmen.

"The governor's staff needs to look into it and perhaps make some tough decisions about leadership," said retired Maj. Gen. Glen W. "Bill" Van Dyke, a past adjutant general of the Guard. "It's crisis management."

That assessment was echoed by other officers and retired military members reacting to the Republic report and to a recent leadership battle among its top commanders.

Retired Col. Karen Bence, who served as mission-support commander for the Guard's 162nd Fighter Wing, said the state military organization suffers from "a severe lack of checks and balances all the way from state headquarters to the Governor's Office."

"If I was governor, I would clean house," Bence added. "Then, I would go after my liaison and say, 'Why didn't I know about this?' "

Bence and Van Dyke said the Guard appears to need an overhaul. Lt. Col. Rob White, who oversees future Guard operations, agreed, saying, "Clean it out at the top."

Brewer serves as commander in chief of the Arizona National Guard.

Details of her organizational review have not been released, but Matthew Benson, a spokesman for the governor, said a top National Guard officer from another state will likely be brought in to conduct a "full, fair and independent review."

Benson added that Brewer still has confidence in Maj. Gen. Hugo Salazar, the state's top military officer, who disputes assertions that the Guard suffers from a flawed culture or disproportionate unethical conduct.

In an interview and an opinion piece published by The Republic on Oct. 8, Salazar described the Arizona National Guard as "one of the nation's best." He acknowledged past problems with the recruiting unit. But he insisted that rogue officers were rooted out, operations were reorganized and a new, agencywide ethics program was created.

"We do not have a corrupt command climate," Salazar said. "We address misconduct. ... It is very unfortunate that the organization is going to be dealt with in that kind of negative perception when in no way is that what the organization is about."

White and numerous colleagues listed a gamut of behavioral problems in recent years -- fraud, sexual harassment, embezzlement, fraternization and retaliation against whistle-blowers -- as evidence to the contrary. Numerous officers said wrongdoing spreads because of lax discipline in an agency that sometimes functions as "a good-old-boy network."

Retired Maj. Glenn MacDonald said the Arizona National Guard produces a steady flow of scandals for his Internet site, militarycorruption.com.

"The nature of National Guards lends itself to cronyism, favoritism and fraud," MacDonald added. "I've seen some of the most incompetent people raised to high ranks simply because they were friends with a governor." A command tussle

A fight between two top commanders pushed Arizona's leadership controversy into the public spotlight last month.

Brig. Gen. Michael Colangelo, who headed the Air National Guard, was fired by Salazar after the Air Force inspector general concluded that Colangelo abused his authority by firing subordinates for misconduct.

Colangelo said he was dismissed for trying to uphold military standards. He said he sought help from Rep. Trent Franks, R-Ariz., and asked Brewer to intervene, but she declined.

"I spent four years in that job trying to reverse a bad culture," Colangelo said. "I was a hired gun brought in to fix problems with the unit. And I paid for it."

Retired Col. Felicia French, who left the Arizona National Guard in 2010 after 32 years of military service, said she believes the organization is laced with corruption and cronyism.

"Without a doubt," French said. "It's different in the regular Army. You're not with the same people all the time. And they (federal military) are harsher. ... The active Army's not nearly this bad."

Col. Louis Jordan Jr., deputy director of the U.S. Army War College's Strategic Studies Institute, said military organizations are a microcosm of society, and when the climate of any unit becomes fouled, the protocol is simple: Allegations get investigated; leaders take remedial action.

Jordan, who served in the Arizona Guard from 2001 to '08, said he is familiar with some of the wrongdoing documented by The Arizona Republic. "It takes human beings to make command decisions," he said. "In this case, that's the adjutant general or governor." A different workplace

In a 2003 paper for the Strategic Studies Institute at the Army War College, Steven M. Jones said healthy organizations breed high ethical expectations and accountability. On the other hand, he wrote, "When the professed principles of leaders do not align with their actual practices, trust and confidence are degraded and overall effectiveness is compromised."

Officers in the regular Army are routinely transferred to new commands worldwide, working with unfamiliar bosses and colleagues. State Guard outfits, by contrast, operate with just a few thousand full-time soldiers and airmen working side by side with little turnover.

Without skills of high value in the civilian market, said Van Dyke, non-commissioned officers cling to comparatively "juicy jobs" in the Guard, especially in a sour economy, creating a network of cronyism.

White said full-time assignment to the Active Guard Reserve is sometimes referred to as "the job-for-life program" because employees so seldom leave. In the state's Air Guard, for example, more than half of full-time officers have been in place at least two decades.

The result is an environment where members build longtime friendships, form rivalries and compete for promotions. They also work long hours -- men and women together -- sometimes on training exercises, where human nature leads to fraternization and affairs.

In that atmosphere, Van Dyke said, leadership is tested when an officer does wrong.

The supervisor responsible for meting out discipline may be a longtime friend of the person needing discipline. The accused might have damaging information about the boss, or connections higher in the chain of command. This sometimes results in a superficial probe and a quiet reprimand that gets torn up months later, or verbal counseling that amounts to a wrist-slap.

"When people work together for so many years, they build up baggage," Van Dyke noted. "It can become a problem."

High-level officers in Arizona's Guard said disciplinary failures are compounded by another concern: Blame for misconduct flows uphill, so a commander who uncovers deep-rooted problems may fear being accused of dereliction.

Moreover, National Guard records reviewed by The Republic indicate that those charged in recent years with misconduct sometimes file countercomplaints against their accusers.

Even when investigations are launched, the Guard's insular nature becomes problematic.

With just 2,376 full-time military personnel -- about the enrollment of an urban high school -- the subset of those qualified to investigate wrongdoing is tiny. Officers know one another or share friends and foes, so investigations may be biased or carry an appearance of unfairness.

Van Dyke said the Guard benefits from a corps of experienced officers who have worked together for years, but it also pays a price. When paychecks and post-retirement pensions are based on rank, keeping a scandal under wraps may benefit friends and avoid taint.

"That's an inherent problem with the National Guard," he said. "Stability is an asset, but it's also a liability. It is very difficult."

Dealing with trouble

The National Guard Bureau, which oversees state military organizations nationwide, declined interview requests and did not respond to questions submitted by e-mail. Instead, a spokeswoman sent this comment:

"The National Guard has been serving this country for more than 375 years and we take that responsibility seriously. Our service members are a representation of society and as such, their successes and failures are a reflection on us all. ... When poor choices are made or problems are brought to our attention, we are just as eager to investigate and take appropriate action to hold members accountable and prevent future infractions."

Experts and insiders said Brewer's planned review may result in efforts to reform the organization, but Guard culture is so resistant to change that even a command shuffle might not succeed.

Van Dyke and others spoke of an unwritten military code that says misconduct -- even felonies -- should be dealt with inside the Guard. Records reviewed by The Republic indicate that some offenses go unreported and that serious wrongdoing is not made public.

White added that fraternization by high-level officers may be quietly resolved with a transfer or retirement. "They just sweep it under the rug," White added. "They claim they're protecting the organization, but they're not. They're protecting themselves."

Salazar defended his Arizona command, saying soldiers and airmen are held accountable. But he said the Guard works under military regulations that give suspected wrongdoers more protections than civilian workers. In all but the most serious cases, for example, discipline is issued to rehabilitate a perpetrator, not as punishment or to set a public example. As a result, even written reprimands are often erased from permanent records within months.

The Arizona National Guard is not alone in grappling with these problems. The California National Guard has been rocked by fraud scandals involving recruiters. Other state organizations have struggled with sexual harassment and assaults.

Only a court-martial or Article 15 proceeding can result in punishment. And legal requirements are so complex, Van Dyke said, "There is a certain avoidance in getting into one of those fur balls." In fact, the Arizona National Guard has never had a successful court-martial, and Article 15 proceedings are rare.

Van Dyke said the overall system may send an unfortunate message: In the National Guard, you can get away with wrongdoing.

Reach the reporter at dennis.wagner@arizonarepublic.com.

Guard at a glance

The Arizona National Guard has more than 9,100 personnel. Nearly 5,200 belong to the Army Guard, 2,477 are in the Air Guard and 1,460 are civilians. Most are part-time service members who have weekend duty or training. The full-time military staffing totals 2,376.

The National Guard system, which evolved from colonial militias, is 375 years old. Nationwide, the Guard is budgeted for 464,900 members: 358,200 in the Army National Guard, and 106,700 in the Air Guard.

Soldiers and airmen deploy on U.S. combat missions as needed, assist in disaster response and serve their respective states in crime-fighting, border security and other roles.

State Guards are headed by the governor (commander in chief) who appoints an adjutant general as the top military officer. When called to serve federally, however, Guard members report through Pentagon channels, ultimately to the president.

Do we really need 9,100 military employees in Arizona???

One good question is why on earth does the state of Arizona need the 9,100 people in the National Guard, of which 2,376 are full time employees? I suspect they all could be fires and the state of Arizona would continue to function without any problems.The Arizona National Guard has more than 9,100 personnel. Nearly 5,200 belong to the Army Guard, 2,477 are in the Air Guard and 1,460 are civilians. Most are part-time service members who have weekend duty or training. The full-time military staffing totals 2,376.

Experts: Arizona National Guard reform hard even with Brewer's support

by Dennis Wagner - Oct. 15, 2012 11:39 PM

<SNIP>

Guard at a glance

The Arizona National Guard has more than 9,100 personnel. Nearly 5,200 belong to the Army Guard, 2,477 are in the Air Guard and 1,460 are civilians. Most are part-time service members who have weekend duty or training. The full-time military staffing totals 2,376.

The National Guard system, which evolved from colonial militias, is 375 years old. Nationwide, the Guard is budgeted for 464,900 members: 358,200 in the Army National Guard, and 106,700 in the Air Guard.

Soldiers and airmen deploy on U.S. combat missions as needed, assist in disaster response and serve their respective states in crime-fighting, border security and other roles.

State Guards are headed by the governor (commander in chief) who appoints an adjutant general as the top military officer. When called to serve federally, however, Guard members report through Pentagon channels, ultimately to the president.