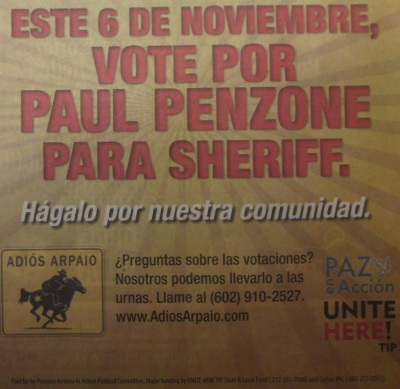

Vote por Penzone para Sheriff

The Arizona National Guard has more than 9,100 personnel. Nearly 5,200 belong to the Army Guard, 2,477 are in the Air Guard and 1,460 are civilians. Most are part-time service members who have weekend duty or training. The full-time military staffing totals 2,376.

Experts: Arizona National Guard reform hard even with Brewer's support

by Dennis Wagner - Oct. 15, 2012 11:39 PM

<SNIP>

More on this topic

Guard at a glance

The Arizona National Guard has more than 9,100 personnel. Nearly 5,200 belong to the Army Guard, 2,477 are in the Air Guard and 1,460 are civilians. Most are part-time service members who have weekend duty or training. The full-time military staffing totals 2,376.

The National Guard system, which evolved from colonial militias, is 375 years old. Nationwide, the Guard is budgeted for 464,900 members: 358,200 in the Army National Guard, and 106,700 in the Air Guard.

Soldiers and airmen deploy on U.S. combat missions as needed, assist in disaster response and serve their respective states in crime-fighting, border security and other roles.

State Guards are headed by the governor (commander in chief) who appoints an adjutant general as the top military officer. When called to serve federally, however, Guard members report through Pentagon channels, ultimately to the president.

General Ahmadzai - “We’re not concerned about getting enough young men, just as long as we get that $4.1 billion a year from NATO.”

From the article it doesn't sound like the American government is running it's occupation of Afghanistan any more efficiently then we ran the occupation of Iraq or Vietnam.

Afghan Army’s Turnover Threatens U.S. Strategy

By ROD NORDLAND

Published: October 15, 2012

KABUL, Afghanistan — The first thing Col. Akbar Stanikzai does when he interviews recruits for the Afghan National Army is take their cellphones.

He checks to see if the ringtones are Taliban campaign tunes, if the screen savers show the white Taliban flag on a black background, or if the phone memory includes any insurgent beheading videos.

Often enough they flunk that first test, but that hardly means they will not qualify to join their country’s manpower-hungry military. Now at its biggest size yet, 195,000 soldiers, the Afghan Army is so plagued with desertions and low re-enlistment rates that it has to replace a third of its entire force every year, officials say.

The attrition strikes at the core of America’s exit strategy in Afghanistan: to build an Afghan National Army that can take over the war and allow the United States and NATO forces to withdraw by the end of 2014. The urgency of that deadline has only grown as the pace of the troop pullout has become an issue in the American presidential campaign.

The Afghan deserters complain of corruption among their officers, poor food and equipment, indifferent medical care, Taliban intimidation of their families and, probably most troublingly, a lack of belief in the army’s ability to fight the insurgents after the American military withdraws.

On top of that, recruits now undergo tougher vetting because of concerns that enemy infiltration of the Afghan military is contributing to a wave of attacks on international forces.

Colonel Stanikzai, a senior official at the army’s National Recruiting Center, is on the front line of that effort; in the six months through September, he and his team of 17 interviewers have rejected 962 applicants, he said.

“There are drug traffickers who want to use our units for their business, enemy infiltrators who want to raise problems, jailbirds who can’t find any other job,” he said. During the same period, however, 30,000 applicants were approved.

“Recruitment, it’s like a machine,” he said. “If you stopped, it would collapse.”

Despite the challenges, so far the Afghan recruiting process is not only on track, but actually ahead of schedule. Afghanistan’s army reached its full authorized strength in June, three months early, though there are still no units that American trainers consider able to operate entirely without NATO assistance.

According to Brig. Gen. Dawlat Waziri, the deputy spokesman for the Afghan Defense Ministry, the Army’s desertion rate is now 7 to 10 percent. Despite substantial pay increases for soldiers who agree to re-enlist, only about 75 percent do, he said. (Recruits commit to three years of service.)

Put another way, a third of the Afghan Army perpetually consists of first-year recruits fresh off a 10- to 12-week training course. And in the meantime, tens of thousands of men with military training are put at loose ends each year, albeit without their army weapons, in a country rife with militants who are always looking for help.

“Fortunately there are a lot of people who want a job with the army, and we’ve always managed to meet the goal set by the Ministry of Defense for us,” said Gen. Abrahim Ahmadzai, the deputy commander of the National Recruiting Center. The country’s 34 provincial recruitment centers have a combined quota of 5,000 new recruits a month.

“We’re not concerned about getting enough young men,” General Ahmadzai said, “just as long as we get that $4.1 billion a year from NATO.”

That is the amount pledged by the United States and its allies to continue paying to cover the expenses of the Afghan military.

In terms of soldiers’ pay, that underwrites $260 a month for the lowest ranks, which in Afghanistan is above-average pay for unskilled labor. A soldier who re-enlists would get a 23 percent raise, to at least $320 a month, more if he had been promoted.

But even as pay rates have risen, so has attrition, which two years ago was 26 percent. The trend is troubling — especially the desertions — as Afghan forces have shouldered an increasing share of the fighting.

American officials have tried to persuade the Afghans to criminalize desertion in an effort to reduce it; instead, Afghan officials have proposed a four-year effort to order the recall of 22,000 deserters, according to General Ahmadzai.

Meanwhile, Afghan deserters live so openly that they list their status as a job reference.

Ghubar, 27, who is from Parwan Province but lives in Kabul, deserted from his battalion with the First Brigade in Kabul just six months into his three-year commitment. Citing his military training, he promptly got a job as a security guard.

Ghubar declined to give more than his first name, but was not worried about being photographed. “There is no accountability,” he said. “If they had any accountability, it wouldn’t be such a bad army.”

Most of his complaints were echoed by the 10 other deserters interviewed on the record for this article.

“I wanted to serve my country, my homeland,” Ghubar said. “But after I joined, I saw the situation was all about corruption. The officers are too busy stealing the money to defeat the insurgents.”

A typical swindle described by the deserters was the diversion of the money allocated to commanders to pay for food, which is usually procured locally rather than distributed from a central depot. “Half the time we would get rice with a bone in it, with a little fat, no meat,” he said.

Ghubar added, “People who join the army, they just lose their hope.”

Ajmal, 24, from Kabul, who also gave only his first name and deserted from the same battalion, said he knew of commanders who had signed up their sons as “ghosts,” enabling them to collect army pay while attending university full time.

Muhammad Fazal Kochai, 28, who deserted from the First Brigade of the 201st Corps a year ago but still proudly shows the army ID card he carries in his wallet, had a particularly rough time. During his year in the army, 25 of his comrades were wounded and 15 killed out of his company of 100 to 150 men, stationed in the dangerous Tangi Wardak area of Wardak Province.

Still, he said, he would have stayed had it not been for the corruption of his officers: “Everybody is trying to make money to line their pockets and build their houses before the Americans leave.”

The final straw came when local villagers pointed him out after his unit had killed a local Taliban commander. “I started to get phone calls from the Taliban saying, ‘We know who you are, and we’re going to kill you.’ ”

He deserted and called to tell the Taliban they did not have to worry about him any longer.

Now Mr. Kochai is convinced the Afghan Army will lose once the Americans leave.

“The army can do nothing on their own without the equipment and supplies of the Americans, without the air support, nothing,” he said.

Sher Agha, 25, from the Sarkano District of eastern Kunar Province, had a similar experience. “Unknown gunmen kept bothering my family and telling them to force me to quit my job and come back home,” he said. Finally, he did.

Most of the deserters either had been wounded or knew someone who had, and they had high marks for the American military’s medical evacuation ability, but complained of poor care and neglect once they were transferred to the Afghan system.

“When I was wounded, the Americans were there in 10 minutes and choppered me out of Khost,” Ajmal said. “Then I went to an Afghan military hospital and no one asked about me. My unit even had me listed as dead.” Someone from his unit did, however, come to retrieve valuable pieces of equipment like his body armor and ammunition belt. He deserted after the hospital discharged him.

At the National Recruiting Center, Colonel Stanikzai keeps working, but he admits to a bleak outlook. “The news of the American withdrawal has weakened our morale and boosted the morale of the enemy,” he said. “I am sorry to speak so frankly. If the international community abandons us again, we won’t be able to last.”

The colonel’s hunt for infiltrators is rooted in realism. Often the Taliban cellphone telltales are adopted by people in rural areas as a protection in case the insurgents stop them, he said, so alone they are hardly grounds for dismissal.

One day last month, his caseload included a convicted murderer from Kunduz: Abdullah, a 30-year-old who has only one name. He had neglected to mention his criminal record, but it was discovered through biometric files compiled with American assistance.

Abdullah pleaded that his offense had been a crime of passion and that the victim’s family had forgiven him and accepted the customary blood money. Colonel Stanikzai sent him back to Kunduz to get a letter from the police chief certifying him for service. Abdullah tried to kiss the colonel’s hand in gratitude.

“We are going through a very, very hard time here,” the colonel said.

From this article it sounds like Emperor Obama is considering drone strikes against Libya, thinking they may help him get reelected in 2012 by being "tough on terrorists".

Of course drone strikes on Libya would be an illegal act of war by the President violating both the U.S. Constitution and International law.

But don't count on the President obeying the law. American Presidents have routinely violated both the U.S. Constitution and International Law many times since World War II, when the American Empire has invaded or bomb countries through out the world.

White House mulls how to strike over Libya attack

Oct. 15, 2012 03:45 PM

Associated Press

WASHINGTON -- The White House has put special operations strike forces on standby and moved drones into the skies above Africa, ready to strike militant targets from Libya to Mali -- if investigators can find the al-Qaida-linked group responsible for the death of the U.S. ambassador and three other Americans in Libya.

But officials say the administration, with weeks until the presidential election, is weighing whether the short-term payoff of exacting retribution on al-Qaida is worth the risk that such strikes could elevate the group's profile in the region, alienate governments the U.S. needs to fight it in the future and do little to slow the growing terror threat in North Africa.

Details on the administration's position and on its search for a possible target were provided by three current and one former administration official, as well as an analyst who was approached by the White House for help. All four spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss the high-level debates publicly.

The dilemma shows the tension of the White House's need to demonstrate it is responding forcefully to al-Qaida, balanced against its long-term plans to develop relationships and trust with local governments and build a permanent U.S. counterterrorist network in the region.

Vice President Joe Biden pledged in his debate last week with Republican vice presidential nominee Paul Ryan to find those responsible for the Sept. 11 attack on the U.S. Consulate in Benghazi that killed Ambassador Chris Stevens and three others.

"We will find and bring to justice the men who did this," Biden said in response to a question about whether intelligence failures led to lax security around Stevens and the consulate. Referring back to the raid that killed Osama bin Laden last year, Biden said American counterterror policy should be, "if you do harm to America, we will track you to the gates of hell if need be."

The White House declined to comment on the debate over how best to respond to the Benghazi attack.

The attack has become an issue in the U.S. election season, with Republicans accusing the Obama administration of being slow to label the assault an act of terrorism early on, and slow to strike back at those responsible.

"They are aiming for a small pop, a flash in the pan, so as to be able to say, 'Hey, we're doing something about it,'" said retired Air Force Lt. Col. Rudy Attalah, the former Africa counterterrorism director for the Department of Defense under President George W. Bush.

Attalah noted that in 1998, after the embassy bombing in Nairobi, the Clinton administration fired cruise missiles to take out a pharmaceutical factory in Sudan that may have been producing chemical weapons for al-Qaida.

"It was a way to say, 'Look, we did something,'" he said.

A Washington-based analyst with extensive experience in Africa said that administration officials have approached him asking for help in connecting the dots to Mali, whose northern half fell to al-Qaida-linked rebels this spring. They wanted to know if he could suggest potential targets, which he says he was not able to do.

"The civilian side is looking into doing something, and is running into a lot of pushback from the military side," the analyst said. "The resistance that is coming from the military side is because the military has both worked in the region and trained in the region. So they are more realistic."

Islamists in the region are preparing for a reaction from the U.S.

"If America hits us, I promise you that we will multiply the Sept. 11 attack by 10," said Oumar Ould Hamaha, a spokesman for the Islamists in northern Mali, while denying that his group or al-Qaida fighters based in Mali played a role in the Benghazi attack.

Finding the militants who overwhelmed a small security force at the consulate isn't going to be easy.

The key suspects are members of the Libyan militia group Ansar al-Shariah. The group has denied responsibility, but eyewitnesses saw Ansar fighters at the consulate, and U.S. intelligence intercepted phone calls after the attack from Ansar fighters to leaders of al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, or AQIM, bragging about it. The affiliate's leaders are known to be mostly in northern Mali, where they have seized a territory as large as Texas following a coup in the country's capital.

But U.S. investigators have only loosely linked "one or two names" to the attack, and they lack proof that it was planned ahead of time, or that the local fighters had any help from the larger al-Qaida affiliate, officials say.

If that proof is found, the White House must decide whether to ask Libyan security forces to arrest the suspects with an eye to extraditing them to the U.S. for trial, or to simply target the suspects with U.S. covert action.

U.S. officials say covert action is more likely. The FBI couldn't gain access to the consulate until weeks after the attack, so it is unlikely it will be able to build a strong criminal case. The U.S. is also leery of trusting the arrest and questioning of the suspects to the fledgling Libyan security forces and legal system still building after the overthrow of Moammar Gadhafi in 2011.

The burden of proof for U.S. covert action is far lower, but action by the CIA or special operations forces still requires a body of evidence that shows the suspect either took part in the violence or presents a "continuing and persistent, imminent threat" to U.S. targets, current and former officials said.

"If the people who were targeted were themselves directly complicit in this attack or directly affiliated with a group strongly implicated in the attack, then you can make an argument of imminence of threat," said Robert Grenier, former director of the CIA's Counterterrorism Center.

But if the U.S. acts alone to target them in Africa, " it raises all kinds of sovereignty issues ... and makes people very uncomfortable," said Grenier, who has criticized the CIA's heavy use of drones in Pakistan without that government's support.

Even a strike that happens with permission could prove problematic, especially in Libya or Mali where al-Qaida supporters are currently based. Both countries have fragile, interim governments that could lose popular support if they are seen allowing the U.S. unfettered access to hunt al-Qaida.

The Libyan government is so wary of the U.S. investigation expanding into unilateral action that it refused requests to arm the drones now being flown over Libya. Libyan officials have complained publicly that they were unaware of how large the U.S. intelligence presence was in Benghazi until a couple of dozen U.S. officials showed up at the airport after the attack, waiting to be evacuated -- roughly twice the number of U.S. staff the Libyans thought were there. A number of those waiting to be evacuated worked for U.S. intelligence, according to two American officials.

In Mali, U.S. officials have urged the government to allow special operations trainers to return, to work with Mali's forces to push al-Qaida out of that country's northern area. AQIM is among the groups that filled the power vacuum after a coup by rebellious Malian forces in March. U.S. special operations forces trainers left Mali just days after the coup. While such trainers have not been invited to return, the U.S. has expanded its intelligence effort on Mali, focusing satellite and spy flights over the contested northern region to track and map the militant groups vying for control of the territory, officials say.

In northern Mali, residents in the three largest cities say they hear the sound of airplanes overhead but can't spot them. That's standard for drones, which are often invisible to the naked eye, flying several thousand feet above ground.

Residents say the plane sounds have increased sharply in recent weeks, following both the attack in Benghazi and the growing calls for a military intervention in Mali.

Chabane Arby, a 23-year-old student from Timbuktu, said the planes make a growling sound overhead. "When they hear them, the Islamists come out and start shooting into the sky," he said.

Aboubacrine Aidarra, another resident of Timbuktu, said the planes circle overhead both day and night. "I have a friend who said he recently saw six at one time, circling overhead. ... They are planes that fly at high altitudes. But they make a big sound. "

Let's outlaw intelligence

Oct. 15, 2012 06:14 PM

To paraphrase Will Rogers, let's outlaw intelligence in America.

If it works as well as prohibition of alcohol in the 1930s did and as well as the "war on drugs" currently does, in five years, we'll be the smartest nation on the planet.

-- Bill Betz, Mesa

I suspect the DEA would love to have 100 sick people be in pain without their medicine if their silly rules would prevent one junkie from getting high.

Let's face it the "War on Drugs" is really a war on the American people and a war on the Bill of Rights.

A New Painkiller Crackdown Targets Drug Distributors

By BARRY MEIER

Published: October 17, 2012

A local druggist in Newport Beach, Calif., never expected that the federal government’s recent crackdown on distributors of prescription painkillers would ensnare him.

But in June, Cardinal Health, a major distributor, abruptly cut off his supplies of narcotics like OxyContin and Percocet. A few months earlier, the Drug Enforcement Administration had accused Cardinal of ignoring signs that some pharmacies in Florida that it supplied with such drugs might be feeding street demand for them.

Cardinal told the druggist, Michael Pavlovich, that the volume of pain drugs and other controlled medications he was dispensing was too high, a situation he said was explainable. His pharmacy specializes in pain patients, he said. Still, it took weeks for Cardinal to start supplying him again, and even then, it limited its shipments to about 15 percent of his previous orders. As a result, Mr. Pavlovich said, many of his patients had to go elsewhere to get prescriptions filled.

“We have to convince them that our dispensing is legitimate,” he said of his dealings with Cardinal.

Cardinal’s crackdown on Mr. Pavlovich was a sign of a new approach by the D.E.A. to stem the growing misuse and abuse of painkillers. In the last decade, the agency has tried a variety of tactics with limited success, from arresting hundreds of doctors to closing scores of pharmacies. Now, it and other agencies are moving up the pharmaceutical food chain, putting pressure on distributors like Cardinal, which act as middlemen between drug makers and the pharmacies and doctors that dispense painkillers.

In response, the distributors are scrambling to limit their liability by more closely monitoring their distribution pipelines and cutting off some customers.

Since January, for example, Cardinal has cut ties with a dozen pharmacies in states including Arizona, California, Nevada and Oklahoma, interviews and court records show. In doing so, the wholesaler, which is based in Columbus, Ohio, cited audits suggesting that people seeking to buy prescription drugs illegally might have targeted the store in question.

Several of the affected drugstores sued Cardinal unsuccessfully to resume supplies, but documents filed in those actions show that until recently, the wholesaler shipped large volumes of pain pills to the stores for months, if not years.

George S. Barrett, Cardinal’s chairman and chief executive, said the company had tightened the criteria it used in determining whether to sell narcotics to a pharmacy. In May, Cardinal settled the action brought by the D.E.A. in connection with its Florida sales by agreeing to suspend shipments of controlled drugs, like narcotics, from a facility in that state for two years. It could also face a significant fine.

“We had a strong antidiversion system in place, but no system is perfect,” Mr. Barrett said. Among other steps, the company said it had created a special committee to regularly evaluate pharmacies that order high volumes of narcotic drugs.

Another major distributor, AmerisourceBergen, recently disclosed that it faces a federal criminal inquiry into its oversight of painkiller sales. And in June, West Virginia officials filed a lawsuit against 14 drug distributors, including Cardinal and AmerisourceBergen, charging that they had fed illicit painkiller use in that state. The companies have denied wrongdoing.

D.E.A. officials have heralded the Cardinal action as the forerunner of a more aggressive approach to the painkiller problem. But critics say that for years, the agency did little to scrutinize distributors who were making tens of millions of dollars from the prescriptions generated by pain clinics in Florida, Ohio and other states. These facilities, often described as “pill mills,” employed doctors who wrote narcotics prescriptions after cursory examinations of patients.

“In the case of West Virginia, they have done nothing,” said a lawyer in Charleston, James M. Cagle, who is working on the state’s action against distributors.

The drug distribution system is a sprawling one that involves about 800 companies, which range in size from a few giants like Cardinal to hundreds of small firms. For wholesalers, the markup on medications can be small, sometimes a few pennies a pill. But with billions of pills sold annually, the profits can be big. Narcotic painkillers are now the most widely prescribed drugs in the United States, with sales last year of $8.5 billion.

This is not the first time the industry has faced scrutiny. In 2008, Cardinal paid $34 million to settle charges that it failed to alert the D.E.A. to suspicious orders for millions of pain pills that it was shipping to Internet pharmacies — operations that for years supplied the illicit market. The same year, another big distributor, McKesson, paid $13 million to settle similar charges. As part of the agreements, both companies denied wrongdoing.

Executives like Mr. Barrett of Cardinal say that it is often difficult for a distributor to tell whether a pharmacy or a doctor is serving legitimate pain patients or supplying illicit drug demand. And distributors have long complained that the D.E.A. has never issued specific guidelines for when they should stop shipping to a customer.

But agency officials say that wholesalers know about the red flags. For example, the agency charged that Cardinal was selling 50 times the amount of pain pills containing the narcotic oxycodone, the active ingredient in OxyContin and other drugs, to its four top pharmacy customers in Florida than it was supplying to the average drugstore in that state.

Cardinal failed to scrutinize such sales, the agency said, even violating the safeguards it promised to put in place when it agreed to settle the government charges in connection with its supplying of Internet pharmacies. “Everyone is making a large amount of money on these drugs,” said Joseph T. Rannazzisi, a deputy assistant administrator of the D.E.A. division that oversees legal drugs, like painkillers.

The D.E.A. is able to track where painkillers are going because distributors regularly file reports detailing their shipments to customers. But just how aggressively the agency uses that data is anyone’s guess.

An agency employee, Michelle Cooper, testified last year that she had attended a training session at which instructors described how investigators like her could use the database to identify suspicious distributors. In doing so, they pointed to data showing that a distributor had suddenly started shipping large and growing volumes of pain pills to Florida drugstores.

It was only later that Ms. Cooper discovered that the case involved a real distributor, not a hypothetical one, and that the company was still making those shipments despite the agency’s apparent awareness of them.

“I didn’t believe the numbers they were showing us were real,” she said. “I thought it was for training purposes.”

Ms. Cooper subsequently investigated the company, Keysource Medical, which agreed last year to give up its license to distribute narcotic drugs.

Faced with Congressional pressure, agency officials like Mr. Rannazzisi have said that they are increasing the ranks of investigators like Ms. Cooper, and that they provide distribution data to state officials when local authorities request it as part of an investigation.

But state officials say it would be more helpful to get that data routinely so they can act more quickly against rogue clinics and pharmacies. For years, Ohio law enforcement authorities did not know which distributors were supplying the many pill mills operating in the state, one official said. If the D.E.A. had supplied that information, “we would have known about the number of shipments going into Ohio and where they were going,” said Aaron Haslam, an assistant state attorney general.

Also, while the D.E.A. brings actions against distributors like Cardinal for failing to notify the agency of a “suspicious order” from a pharmacy or other customer, it does not share those reports with officials in the state where the pharmacy is based.

In response to a request from The New York Times, the agency even declined to disclose the number of such reports it received annually. A spokeswoman, Barbara Carreno, said in a statement that the agency considered such statistics “law enforcement sensitive” information, but she did not elaborate.

The Times has filed a Freedom of Information Act request seeking that data.

Fair trial. Ask the CIA if you deserve a "fair trial" and they will tell

you that you won't get a fair trail if they decide you are a criminal.

The CIA will give you a fair chance to run from a drone launched

missile if they decide to execute you for crimes you have allegedly committed.

I can only wonder when the DEA will be requesting drones to executed suspected drug dealers with!

CIA seeks to expand drone fleet, officials say

By Greg Miller, Published: October 18

The CIA is urging the White House to approve a significant expansion of the agency’s fleet of armed drones, a move that would extend the spy service’s decade-long transformation into a paramilitary force, U.S. officials said.

The proposal by CIA Director David H. Petraeus would bolster the agency’s ability to sustain its campaigns of lethal strikes in Pakistan and Yemen and enable it, if directed, to shift aircraft to emerging al-Qaeda threats in North Africa or other trouble spots, officials said.

If approved, the CIA could add as many as 10 drones, the officials said, to an inventory that has ranged between 30 and 35 over the past few years.

The outcome has broad implications for counterterrorism policy and whether the CIA gradually returns to being an organization focused mainly on gathering intelligence, or remains a central player in the targeted killing of terrorism suspects abroad.

In the past, officials from the Pentagon and other departments have raised concerns about the CIA’s expanding arsenal and involvement in lethal operations, but a senior Defense official said that the Pentagon had not opposed the agency’s current plan.

Officials from the White House, the CIA and the Pentagon declined to comment on the proposal. Officials who discussed it did so on the condition of anonymity, citing the sensitive nature of the subject.

One U.S. official said the request reflects a concern that political turmoil across the Middle East and North Africa has created new openings for al-Qaeda and its affiliates.

“With what happened in Libya, we’re realizing that these places are going to heat up,” the official said, referring to the Sept. 11 attack on a U.S. diplomatic outpost in Benghazi. No decisions have been made about moving armed CIA drones into these regions, but officials have begun to map out contingencies. “I think we’re actually looking forward a little bit,” the official said.

White House officials are particularly concerned about the emergence of al-Qaeda’s affiliate in North Africa, which has gained weapons and territory following the collapse of the governments in Libya and Mali. Seeking to bolster surveillance in the region, the United States has been forced to rely on small, unarmed turboprop aircraft disguised as private planes.

Meanwhile, the campaign of U.S. airstrikes in Yemen has heated up. Yemeni officials said a strike on Thursday — the 35th this year — killed at least seven al-Qaeda-linked militants near Jaar, a town in southern Yemen previously controlled by al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, as the terrorist group’s affiliate is known.

The CIA’s proposal would have to be evaluated by a group led by President Obama’s counterterrorism adviser, John O. Brennan, officials said.

The group, which includes senior officials from the CIA, the Pentagon, the State Department and other agencies, is directly involved in deciding which alleged al-Qaeda operatives are added to “kill” lists. But current and former officials said the group also plays a lesser-known role as referee in deciding the allocation of assets, including whether the CIA or the Defense Department takes possession of newly delivered drones.

“You have to state your requirements and the system has to agree that your requirements trump somebody else,” said a former high-ranking official who participated in the deliberations. “Sometimes there is a food fight.”

The administration has touted the collaboration between the CIA and the military in counterterrorism operations, contributing to a blurring of their traditional roles. In Yemen, the CIA routinely “borrows” the aircraft of the military’s Joint Special Operations Command to carry out strikes. The JSOC is increasingly engaged in activities that resemble espionage.

The CIA’s request for more drones indicates that Petraeus has become convinced that there are limits to those sharing arrangements and that the agency needs full control over a larger number of aircraft.

The U.S. military’s fleet dwarfs that of the CIA. A Pentagon report issued this year counted 246 Predators, Reapers and Global Hawks in the Air Force inventory alone, with hundreds of other remotely piloted aircraft distributed among the Army, the Navy and the Marines.

Petraeus, who had control of large portions of those fleets while serving as U.S. commander in Iraq and Afghanistan, has had to adjust to a different resource scale at the CIA, officials said. The agency’s budget has begun to tighten, after double-digit increases over much of the past decade.

“He’s not used to the small budget over there,” a U.S. congressional official said. In briefings on Capitol Hill, Petraeus often marvels at the agency’s role relative to its resources, saying, “We do so well with so little money we have.” The official declined to comment on whether Petraeus had requested additional drones.

Early in his tenure at the CIA, Petraeus was forced into a triage situation with the agency’s inventory of armed drones. To augment the hunt for Anwar al-Awlaki, a U.S.-born cleric linked to al-Qaeda terrorist plots, Petraeus moved several CIA drones from Pakistan to Yemen. After Awlaki was killed in a drone strike, the aircraft were sent back to Pakistan, officials said.

The number of strikes in Pakistan has dropped from 122 two years ago to 40 this year, according to the New America Foundation. But officials said the agency has not cut back on its patrols there, despite the killing of Osama bin Laden and a dwindling number of targets.

The agency continues to search for bin Laden’s successor, Ayman al-Zawahiri, and has carried out dozens of strikes against the Haqqani network, a militant group behind attacks on U.S. forces in Afghanistan.

The CIA also maintains a separate, smaller fleet of stealth surveillance aircraft. Stealth drones were used to monitor bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. Their use in surveillance flights over Iran’s nuclear facilities was exposed when one crashed in that country last year.

Any move to expand the reach of the CIA’s fleet of armed drones probably would require the agency to establish additional secret bases. The agency relies on U.S. military pilots to fly the planes from bases in the southwestern United States but has been reluctant to share overseas landing strips with the Defense Department.

CIA Predators that are used in Pakistan are flown out of airstrips along the border in Afghanistan. The agency opened a secret base on the Arabian Peninsula when it began flights over Yemen, even though JSOC planes are flown from a separate facility in Djibouti.

Karen DeYoung contributed to this report.

This water is not part of the US, but the American military seems to have decided that it is the US Military's job to police it.

As H. L. Mencken said:

In a warming Arctic, U.S. faces new security and safety concerns

By Kim Murphy, Los Angeles Times

October 19, 2012, 6:00 a.m.

BARROW, Alaska — In past years, these remote gray waters of the Alaskan Arctic saw little more than the occasional cargo barge and Eskimo whaling boat. No more.

This summer, when the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Bertholf was monitoring shipping traffic along the desolate tundra coast, its radar displays were often brightly lighted with mysterious targets.

There were oil drilling rigs, research vessels, fuel barges, small cruise ships. A few were sailboats that had ventured through the Northwest Passage above Canada. On a single day in August, 95 ships were detected between Prudhoe Bay and Wainwright off America's least defended coastline, and for some of them, Coast Guard officials had no idea what the vessels were carrying or who was on them.

"There's probably 1,500 people out there," Rear Adm. Thomas P. Ostebo, commander of the Coast Guard's 17th District in Alaska, said at a recent conference of Arctic policymakers near Anchorage. "It's kind of spinning a little bit out of control."

The rapid melting of the polar ice cap is turning the once ice-clogged waters off northern Alaska into a navigable ocean, and the rush to grab the region's abundant oil and mineral resources by way of new shipping lanes is posing safety and security concerns for Coast Guard patrols.

What happens if a cruise ship gets stranded in stray ice? Or if a sailing vessel capsizes off an uninhabited coast?

"Yesterday, we saw three sailing vessels in 24 hours," said the Bertholf's commander, Capt. Thomas E. Crabbs.

The Coast Guard this summer ran Arctic Shield, the most extensive patrol operation it has ever mounted in the Arctic. It set up a temporary operating base and remote communications station at Barrow.

A fleet of cutters, buoy tenders, helicopters and boarding vessels deployed across the Beaufort, Chukchi and Bering seas to oversee new offshore oil drilling operations offers search-and-rescue if needed and provides notice to burgeoning ship traffic that the U.S. is monitoring its northernmost border.

The rush for riches as Russia, Norway and Canada vie with the U.S. for the Arctic's mineral resources, and the possibility that drug dealers, arms merchants and terrorists could begin to explore transport routes near America's largest oil fields have prompted the U.S. military to begin planning for a future in the Arctic much more substantial than it had envisioned.

The U.S. Naval War College last year conducted war games simulating the sinking of a ship carrying weapons of mass destruction from North Africa to Asia across the top of Canada and Alaska.

The Air Force has been practicing how to make food and survival gear drops to survivors of a large plane crash in the unbelievably remote Brooks Range, north of Fairbanks.

The North American Aerospace Defense Command, known as NORAD, already has gone beyond drills: F-15 fighters have been launched on interceptions at least 50 times during the last five years in response to Russian long-range bombers — not previously seen here since the Cold War — which have been provocatively skirting the edges of U.S. airspace.

Through it all, U.S. security forces are battling historically sketchy radio communications, vicious storms, shifting ice floes and huge distances from base: Coast Guard cutters must sail 1,200 miles south just to take on food and refuel.

"All of the uniqueness of operating up in the Arctic represents huge challenges for us," said Royal Canadian Air Force Col. Dan Constable, deputy commander of NORAD's Alaska region.

The Naval War College games in September 2011 were an early test, and not an encouraging one. Many of the scenarios rehearsed, former Navy Cmdr. Christopher Gray said, ran into problems with poor communications and trouble maintaining supplies of food, fuel and supplies.

"Does the Navy have the ability to go up and operate a number of ships, a number of aircraft, for a sustained period of time in this environment, where it's cold, it's got bad weather, it's got a lot of ice, and it's really far away from everything that supports you? What we found is that the answer is, not really," Gray said.

The Bertholf is especially suited to summertime operations in the Far North. Though not capable of operating in ice, it is equipped with high-efficiency engines and stability systems that allow the vessel and its crew of 146 to remain in the Arctic for a month at a time — heretofore unheard of in the U.S. fleet.

"Because we're present here and because we have the endurance to remain here throughout the season, we're going to be able to understand who is in the maritime domain," Crabbs said as a small vessel carrying boarding troops was launched off the Bertholf's stern for a closer look at nearby shipping traffic.

U.S. officials say they are still several decades away from needing a full-scale military presence in the region, and with luck, there will be no need to resort to arms: The real source of conflict is the battle everyone faces — with the elements.

"If somebody were to invade the Canadian High North," Canadian Forces chief of staff Gen. Walter Natynczyk said at the Arctic Imperative Summit, "my first problem would be to rescue them."

***

The move to secure the Arctic goes well beyond domestic security. With easier access to the more than 90 billion barrels of oil and trillions of cubic feet of natural gas in the Arctic, nations are rushing to gain international recognition of territorial claims, mineral contracts and shipping routes.

On Aug. 2, the Chinese icebreaker Snow Dragon completed an unprecedented voyage across the top of the world through the Northwest Passage.

Icelandic President Olafur Ragnar Grimsson was paid a visit by a delegation of senior Chinese officials who wanted to discuss Beijing's bid for permanent observer status in the Arctic Council, the suddenly powerful organization of eight nations with territory in the Arctic Circle.

"And China is not the only Asian country interested in the Arctic," Grimsson said at the Arctic summit. Singapore and South Korea, he said, also want in.

The U.S. has been slow to stake out its own territory. While Russia has submitted a claim for thousands of miles of seabed, and Canada is asserting title to mineral-rich areas along the U.S. border, the United States is the only Arctic nation that has not ratified the 1982 treaty known as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea — the international mechanism for brokering such claims.

The U.S. has also fallen behind on what the Coast Guard needs to patrol the new mineral development zones. The only working icebreaker is the cutter Healy, with a second being refurbished that is due to return soon. Russia, by contrast, has 25 icebreakers, according to the U.S. Congressional Research Service. Finland and Sweden have seven each, Canada six.

"I think it's a real-time imperative for our nation to get its arms around these things," Rear Adm. Ostebo said. "It's critically important to understand that we do not control it. The rest of the world has a boat here, and we are late to the table."

kim.murphy@latimes.com

Do we really need 9,100 military employees in Arizona???

One good question is why on earth does the state of Arizona need the 9,100 people in the National Guard, of which 2,376 are full time employees? I suspect they all could be fires and the state of Arizona would continue to function without any problems.

Afghan Army’s Turnover Threatens U.S. Strategy

Sounds like the "war in Afghanistan" is really an American welfare program for the puppet government we installed in Afghanistan.

Will Obama bomb Libya to get reelected???

Will Obama order drone strikes on Libya to get reelected in 2012?

Let's outlaw intelligence

Source

DEA Painkiller Crackdown Targets Drug Distributors

DEA Painkiller Crackdown Targets Drug Distributors

CIA wants drones to kill with

CIA wants drones so it can be the judge, jury and executioner??

US military creates job program for itself in Arctic??

A jobs program the military created for it's self???

"The whole aim of practical politics is to keep the populace alarmed (and hence clamorous to be led to safety) by menacing it with an endless series of hobgoblins, all of them imaginary."

Source

Were some issues missing from these debates?

Some choice for President - Obamney or Rombama - forget Gary Johnson or Jill Stein. In this editorial Vin points out that the Presidential debates are rigged to exclude third parties like Gary Johnson from the Libertarian Party and Jill Stein from the Green Party.Hey, we all know that either Obamney or Rombama is going to win the election, so what hard could there be in letting the Libertarians and Greens into the debate. It would give us some new interesting ideas.

Like legalizing drugs, ending the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and repealing the unconstitutional Patriot Act.

Sheriff Joe's IT guy

And no I don't work for Sheriff Joe and wouldn't work for him if you paid me.

Let's hope Sheriff Joe loses this election and is replaced by Paul Penzone.

Of course Paul Penzone isn't much better then Sheriff Joe, but it certainly would be nice to get rid of Sheriff Joe who has been terrorizing the citizens of Maricopa County for the last 20 years.

AG Tom Horne redacts anything that makes him look bad???

Remember Arizona Attorney General Tom Horne is the guy who asked Governor Jan Brewer to declare Prop 203 null and void so he could arrest medical marijuana patients.I bet that was a smoke screen to cover up his crimes.

Redacted parts of AG Office documents allege impropriety

By Yvonne Wingett Sanchez The Republic | azcentral.com Tue Oct 23, 2012 12:34 AM

The Arizona Attorney General’s Office redacted allegations about an alleged affair between Tom Horne and one of his subordinates, and disparaging information about another employee and political ally, a comparison of documents shows.

The Arizona Attorney General’s Office redacted allegations about an alleged affair between Tom Horne and one of his subordinates, and disparaging information about another employee and political ally, a comparison of documents shows.

The redactions could violate state public-records law, some legal experts say.

The Arizona Public Records Law requires state and local government agencies to make various public records open for inspection by any person unless it is confidential by law, or if privacy interests outweigh the public’s interest or if disclosure is not in the state’s best interest.

The Attorney General’s Office in August produced for The Arizona Republic and other media hundreds of records that stemmed from a 2011 internal investigation Horne ordered into suspected media leaks. The records included eight memos — some with large areas redacted — summarizing interviews of attorney-general employees by Horne’s investigator, Margaret “Meg” Hinchey.

Earlier this month, the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office produced unredacted versions of six Hinchey memos as part of the records it released tied to an investigation into alleged campaign-finance violations by Horne and his employee Kathleen Winn. County Attorney Bill Montgomery has accused the pair of illegally coordinating tactics during the 2010 election with an independent-expenditure committee Winn chaired. Horne and Winn deny the allegations and have vowed to fight them in court.

A comparison of the two versions of six memos shows the Attorney General’s Office redacted information about an alleged personal relationship between Horne, a married man, and Assistant Attorney General Carmen Chenal, a long-time Horne employee and confidant.

The office also redacted an employee statement that focused on Winn performing private work on government time — a practice that Horne personally sanctioned — as well as remarks witnesses made about Winn’s behavior.

When asked Monday if he would comment on the personal allegations against him, Horne responded via text, “Cole’s characterization is appropriate.”

Arizona Solicitor General David Cole, who oversaw the redactions, said “speculative, mean spirited, nasty gossip that can be false and that can be the subject of lawsuits for defamation does not serve the public interest.”

Chenal could not be reached for comment late Monday.

Winn said statements made by witnesses about her were false, describing one witness as “mentally unstable,” and Hinchey as a sloppy investigator who must not have fully understood witnesses’ statements.

Amy Rezzonico, Horne’s spokeswoman, said the redactions were consistent with state law, and based on privacy, confidentiality and the best interests of the state. In an e-mailed statement, she wrote it is office policy “to redact information that is known to be defamatory and false. It is also the policy of this office to redact extraneous gossip, innuendo, rumors, and hurtful remarks that have nothing to do with the legitimate functions of the agency and that can cause damage to individuals and the agency.”

First Amendment lawyers and experts, however, said the records shed light on the conduct of public officials and should not be redacted.

“The courts have consistently held that just because something is embarrassing to a public official does not mean that it should not be released as part of a public-records request,” said lawyer Dan Barr, who reviewed both versions of the memos. “The best interests of the state do not equate with the best interests of public officials.”

Lawyers also pointed to the attorney general’s own handbook, a guide for agencies to use when determining which documents are subject to public scrutiny under the Arizona Public Records Law. That handbook specifically cites one Arizona court, which found, “The cloak of confidentiality may not be used, however, to save an officer or public body from inconvenience or embarrassment.”

Cole, who reports to Horne, said Horne was not involved in deciding what information was redacted.

Cole wrote in an e-mail to The Republic that he has a public-records committee comprised of seasoned lawyers to ensure the agency follows the law. He cited case law that he believes shows his office acted properly in redacting the material.

Kathryn Marquoit, assistant ombudsman for public access at the state ombudsman’s office, has not reviewed the redactions. Generally, she said, agencies must find that it would be an invasion of privacy before it redacts such information.

“Just because it’s personal information doesn’t necessarily mean it’s an invasion of privacy,” she said, saying in this case, the agency appears to try to make a case that the information is not public because it does not deal with the public business.

“But I think that’s a tough argument to make,” she said.

In July 2011, Horne handpicked Hinchey to conduct a confidential internal investigation to determine if someone within the office had leaked information to the PhoenixNew Times regarding his hiring of Chenal despite a history of problems with her law license. Hinchey interviewed numerous employees, obtained access to staff phone records and e-mails, and searched Winn’s office once she became the suspected source of the leak.

The Attorney General’s Office’s redactions to Hinchey’s notes included:

Numerous references to an alleged affair between Horne and Chenal. Lucia de Vernai, a legal assistant, stated she heard Winn mention the rumor of an affair between Horne and Chenal five to ten times.

Assistant Attorney General Michael Flynn recalled another employee telling him about a video of Horne and Chenal walking together and that “Horne’s arms swung in a manner, that just prior to going off camera, that one might think AG Horne was about to give Chenal a ‘butt pat.’”

Numerous references to employees dislike of Winn because of her alleged “jealousy” of other women she perceived to be close to Horne, her alleged treatment of other employees and Winn’s alleged giddiness after the New Times wrote a story about the alleged affair between Horne and Chenal.

Linnea Heap, a collector in the agency, stated Winn made “snarky” comments about Heap’s friendship with Chenal and said Winn talked about being contacted by a reporter about “the rumor of an affair” between Chenal and Horne.

Heap also recalled a conversation with Winn during the 2010 campaign, according to the notes. “Heap indicated that she thinks Winn desires the attention and that it seems she is now trying to be ‘Mrs. AG,’” the notes stated.

Winn told The Republic she is happily married and is not jealous of any women at the office.

“I’m very secure in who I am,” she said. “I have a great relationship with the AG.”

De Vernai recalled a conversation she had with Winn, in which she said Winn stated, “C’mon. If Tom was going to have an affair, who do you think he would have one with? Carmen or me?”

De Vernai also recalled a dinner, where Winn told her, Chenal and one other woman, “I’m the new girlfriend. You’re the crabby old one.” De Vernai said the other woman, who helped out during the 2010 election, responded she would “arm wrestle” Winn for Horne.

Winn said she did not say that.

Numerous references to employees’ exasperation with Winn, whom one employee alleged inserts herself into work-related matters she was not qualified to handle. For example, Flynn was uncomfortable that Winn allegedly gave her personal cellphone number to a juvenile who sought her advice on an incident while attending a “sexting” lecture. “Flynn does not think Winn should have done that as she makes herself a witness to a crime and likely is not qualified to provide such ‘counseling,’” Hinchey’s notes read.

Flynn also told Hinchey he had the impression Winn thinks she is a “cop, an attorney and a counselor.” Hinchey wrote Flynn was aware of Winn “conducting her own investigation into some party level activity related to precinct party voting.”

Former Assistant Attorney General Gerald Richard told Hinchey that Winn once asked him to get Chenal to use her relationship with Horne to get Winn a raise. Winn earns an annual salary of about $100,000.

Winn said she does not recall that conversation.

De Vernai said she believed Winn, who has a real-estate-related background, “solicits employees” as clients, and that she has reported concerns about Winn twice to Horne who responded he “won’t fire her.”

Winn said she has never solicited work from employees. Records provided to The Republic in the past show Horne allowed Winn to perform private real-estate-related work on government time.

Tom Horne's office withholds public information to protect ... Tom Horne

Remember Tom Horne is the guy who asked Governor Jan Brewer to declare Prop 203 null and void so he could continue arresting medical marijuana smokers.I bet that was a smoke screen to cover up his crimes.

Tom Horne's office withholds public information to protect ... Tom Horne

By LAURIE ROBERTS

Mon, Oct 22 2012

We take you now to the latest in As the State Spins, the daytime drama starring everybody’s favorite attorney general, Tom Horne.

We take you now to the latest in As the State Spins, the daytime drama starring everybody’s favorite attorney general, Tom Horne.

When we last left our story, we had learned that our hero was suspected of having an affair with an assistant attorney general he’d hired – a woman whose qualifications were, let’s just say, less than impressive. And, that Horne and another of his hires – a women who ran a supposedly independent campaign to help get him elected – have been accused of violating campaign-finance laws.

The state’s top law enforcement official has dodged accusations of an affair and denied trying to cheat his way into office by coordinating with a supposedly “independent” campaign that was pouring money into his 2010 election bid.

Which brings us to today’s episode: Public Records, Schmublic Records…. in which we learn that the Attorney General’s Office has been hiding records about embarrassing stuff. Things like his rumored affair with Assistant Attorney General Carmen Chenal and questions about the on-the-job conduct of Kathleen Winn, his campaign ally-turned-community-outreach-coordinator.

The story actually began in July 2011, when New Times columnist Stephen Lemons questioned why Horne would hire Chenal given that she had, among other things, long ago been suspended from practicing law.

(That is, until Horne helped her get her license back. She’s now on probation while serving as an assistant attorney general.)

Horne immediately launched an internal investigation. No, not to find out why his office was paying a six-figure salary to a woman who had questionable credentials, but to find the source of the leak to Lemons.

Instead, the investigator found evidence suggesting that Horne had violated state law by coordinating with Winn’s independent campaign. In August, Horne’s office released results of the leak investigation, as Arizona’s Public Records Law required. But the records were heavily censored.

Earlier this month, we found out why. That’s when Maricopa County Attorney Bill Montgomery, in announcing that Horne and Winn had violated campaign-finance laws, released a clean copy of the records.

Turns out all those pages blacked out by the Attorney General’s Office contained interviews with staffers who talked of Horne’s rumored long-time affair with Chenal. Of reports that Winn was calling herself Horne’s “new girlfriend” and “inserting herself” into cases where she had no business, given that she is neither an attorney nor an investigator. Of concerns that Winn was working on her mortgage broker business on state time.

Horne spokeswoman Amy Rezzonico said in an e-mail that the records were withheld “on the bases of privacy, confidentiality and best interests of the state.”

Indeed, the Arizona Supreme Court has said that records may be withheld “where recognition of the interests of privacy, confidentiality or the best interest of the state in carrying out its legitimate activities outweigh the general policy of open access.”

The court also has said the state must “specifically demonstrate how production of the documents would violate the rights of privacy or confidentiality or would be detrimental to the best interests of the state.”

The question here is, was Horne’s interest in keeping this stuff quiet in the best interest of the state? Or in the best interest of Horne?

Two experts on Arizona’s Public Records Law tell me there was no legitimate reason to withhold what were clearly public records.

“The courts have held that embarrassment for a public official is not a reason to redact information,” said attorney Dan Barr, who represents the First Amendment Coalition of Arizona.

Attorney David Bodney, who represents The Republic and 12News, called it “a risky overbroad approach to public information that prohibits the ability of the public to monitor the conduct.”

The people who control the information, however, seem to think it’s perfectly acceptable to pick and choose what you and I get to know about how the chief law enforcement agency in the state is operated. Horne’s solicitor general, Dave Cole, said in an e-mail that a committee of lawyers in the Attorney General’s Office decided not to disclose the information and that Horne wasn’t involved in the decision.

“Speculative, mean spirited nasty gossip that can be false and that can be the subject of lawsuits for defamation does not serve the public interest,” Cole said.

Translation, Horne’s people weren’t protecting Horne. Or his assistant attorney general/rumored girlfriend. Or his campaign pal who now does…whatever it is she does over there at the Attorney General’s Office.

No, they were protecting us.

Really, they were.

As the state spins, you see, it also unravels.

Maybe a good way to reduce crime would be to fire all the cops who are tricking people into committing crimes. That would certainly reduce the crime rate.

And of course I suspect the FBI and Homeland Security is doing the same stuff at the Federal level. I have posted a number of article where the FBI has created bomb plots and then arrested people the tricked into participating in the fake bomb plots.

N.Y. police informant: Paid for ‘baiting’ Muslims

By Matt Apuzzo Associated Press Tue Oct 23, 2012 7:28 AM

NEW YORK — A paid informant for the New York Police Department’s intelligence unit was under orders to “bait” Muslims into saying bad things as he lived a double life, snapping pictures inside mosques and collecting the names of innocent people attending study groups on Islam, he told The Associated Press.

Shamiur Rahman, a 19-year-old U.S. citizen of Bengali descent who has now denounced his work as an informant, said police told him to embrace a strategy called “create and capture.” He said it involved creating a conversation about jihad or terrorism, then capturing the response to send to the NYPD. For his work, he earned as much as $1,000 a month and goodwill from the police after a string of minor marijuana arrests.

“We need you to pretend to be one of them,” Rahman recalled the police telling him. “It’s street theater.”

Rahman, who said he plans to move to the Caribbean, said he now believes his work as an informant against Muslims in New York was “detrimental to the Constitution.” After he disclosed to friends details about his work for the police — and after he told the police that he had been interviewed by the AP — he stopped receiving text messages from his NYPD handler, “Steve,” and his handler’s NYPD phone number was disconnected.

Rahman’s account shows how the NYPD unleashed informants on Muslim neighborhoods, often without specific targets or criminal leads. Much of what Rahman said represents a tactic the NYPD has denied using.

The AP corroborated Rahman’s account through arrest records and weeks of text messages between Rahman and his police handler. The AP also reviewed the photos Rahman sent to police. Friends confirmed Rahman was at certain events when he said he was there, and former NYPD officials, while not personally familiar with Rahman, said the tactics he described were used by informants.

Informants like Rahman are a central component of the NYPD’s wide-ranging programs to monitor life in Muslim neighborhoods since the 2001 terrorist attacks. Police officers have eavesdropped inside Muslim businesses, trained video cameras on mosques and collected license plates of worshippers. Informants who trawl the mosques — known informally as “mosque crawlers” — tell police what the imam says at sermons and provide police lists of attendees, even when there’s no evidence they committed a crime.

The programs were built with unprecedented help from the CIA.

Police recruited Rahman in late January, after his third arrest on misdemeanor drug charges, which Rahman believed would lead to serious legal consequences. An NYPD plainclothes officer approached him in jail and asked whether he wanted to turn his life around.

The next month, Rahman said, he was on the NYPD’s payroll.

NYPD spokesman Paul Browne did not immediately return a message seeking comment Tuesday. He has denied widespread NYPD spying, saying police only follow leads.

In an Oct. 15 interview with the AP, however, Rahman said he received little training and spied on “everything and anyone.” He took pictures inside the many mosques he visited and eavesdropped on imams. By his own measure, he said he was very good at his job and his handler never once told him he was collecting too much, no matter whom he was spying on.

Rahman said he thought he was doing important work protecting New York City and considered himself a hero.

One of his earliest assignments was to spy on a lecture at the Muslim Student Association at John Jay College in Manhattan. The speaker was Ali Abdul Karim, the head of security at the Masjid At-Taqwa mosque in Brooklyn. The NYPD had been concerned about Karim for years and already had infiltrated the mosque, according to NYPD documents obtained by the AP.

Rahman also was instructed to monitor the student group itself, though he wasn’t told to target anyone specifically. His NYPD handler told him to take pictures of people at the events, determine who belonged to the student association and identify its leadership.

On Feb. 23, Rahman attended the event with Karim and listened, ready to catch what he called a “speaker’s gaffe.” The NYPD was interested in buzz words such as “jihad” and “revolution,” he said. Any radical rhetoric, the NYPD told him, needed to be reported.

Talha Shahbaz, then the vice president of the student group, met Rahman at the event. As Karim was finishing his talk on Malcolm X’s legacy, Rahman told Shahbaz that he wanted to know more about the student group. They had briefly attended the same high school.

Rahman said he wanted to turn his life around and stop using drugs, and said he believed Islam could provide a purpose in life. In the following days, Rahman friended him on Facebook and the two exchanged phone numbers. Shahbaz, a Pakistani who came to the U.S. more three years ago, introduced Rahman to other Muslims.

“He was telling us how he loved Islam and it’s changing him,” said Asad Dandia, who also became friends with Rahman.

Secretly, Rahman was mining his new friends for details about their lives, taking pictures of them when they ate at restaurants and writing down license plates on the orders of the NYPD.

On the NYPD’s instructions, he went to more events at John Jay, including when Siraj Wahhaj spoke in May. Wahhaj, 62, is a prominent but controversial New York imam who has attracted the attention of authorities for years. Prosecutors included his name on a list of people they said “may be alleged as co-conspirators” in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, though he was never charged. In 2004, the NYPD placed Wahhaj on an internal terrorism watch list and noted: “Political ideology moderately radical and anti-American.”

That evening at John Jay, a friend took a photograph of Wahhaj with a grinning Rahman.

Rahman said he kept an eye on the MSA and used Shahbaz and his friends to facilitate traveling to events organized by the Islamic Circle of North America and Muslim American Society. The society’s annual convention in Connecticut draws a large number of Muslims and plenty of attention from the NYPD. According to NYPD documents obtained by the AP, the NYPD sent three informants there in 2008 and was keeping an eye on the group’s former president.

Rahman was told to spy on the speakers and collect information. The conference was called “Defending Religious Freedom.” Shahbaz paid Rahman’s travel expenses.

Rahman said he never witnessed any criminal activity or saw anybody do anything wrong.

He said he sometimes intentionally misinterpreted what people had said. For example, Rahman said he would ask people what they thought about the attack on the U.S. Consulate in Libya, knowing the subject was inflammatory. It was easy to take statements out of context, he said. He said wanted to please his NYPD handler, whom he trusted and liked.

“I was trying to get money,” Rahman said. “I was playing the game.”

Rahman said police never discussed the activities of the people he was assigned to target for spying. He said police told him once, “We don’t think they’re doing anything wrong. We just need to be sure.”

On some days, Rahman spent hours and covered miles in his undercover role. On Sept. 16, for example, he made his way in the morning to the Al Farooq Mosque in Brooklyn, snapping photographs of an imam and the sign-up sheet for those attending a regular class on Islamic instruction. He also provided their cell phone numbers to the NYPD. That evening he spied on people at Masjid Al-Ansar, also in Brooklyn.

Text messages on his phone showed that Rahman also took pictures last month of people attending the 27th annual Muslim Day Parade in Manhattan. The parade’s grand marshal was New York City Councilman Robert Jackson.

Rahman said he eventually tired of spying on his friends, noting that at times they delivered food to needy Muslim families. He said he once identified another NYPD informant spying on him. He took $200 more from the NYPD and told them he was done as an informant. He said the NYPD offered him more money, which he declined. He told friends on Facebook in early October that he had been a police spy but had quit. He also traded Facebook messages with Shahbaz, admitting he had spied on students at John Jay.

“I was an informant for the NYPD, for a little while, to investigate terrorism,” he wrote on Oct. 2. He said he no longer thought it was right. Perhaps he had been hunting terrorists, he said, “but I doubt it.”

“I hated that I was using people to make money,” Rahman said. “I made a mistake.”

The Top 20 Airports for TSA Theft

By MEGAN CHUCHMACH | ABC News

Your suitcase has been tagged and whisked away for a TSA security check before being loaded onto a plane en route to your final destination. How safe are the belongings inside? The TSA has fired nearly 400 employees for allegedly stealing from travelers, and for the first time, the agency is revealing the airports where those fired employees worked.

Newly released figures provided to ABC News by the TSA in response to a Freedom of Information Act request show that, unsurprisingly, many of the country's busiest airports also rank at the top for TSA employees fired for theft.

Sixteen of the top 20 airports for theft firings are also in the top 20 airports in terms of passengers passing through.

At the head of the list is Miami International Airport, which ranks twelfth in passengers but first in TSA theft firings, with 29 employees terminated for theft from 2002 through December 2011. JFK International Airport in New York is second with 27 firings, and Los Angeles International Airport is third with 24 firings. JFK ranks sixth in passenger traffic, while LAX is third. Chicago, while second in traffic, ranked 20th in theft firings.

The four airports listed in the TSA's top 20 list of employee firings for theft that aren't also among the FAA's top 20 for passenger activity are Salt Lake City International, Washington Dulles, Louis Armstrong New Orleans International, and San Diego International.

The top airports across the U.S. for TSA employees fired for theft are:

1. Miami International Airport (29)

2. JFK International Airport (27)

3. Los Angeles International Airport (24)

4. Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport (17)

5. Las Vegas-McCarren International Airport (15)

6. Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport and New York-Laguardia Airport (14 each)

8. Newark Liberty, Philadelphia International, and Seattle-Tacoma International airports (12 each)

11. Orlando International Airport (11)

12. Houston-George Bush Intercontinental Airport and Salt Lake City International Airport (10 each)

14. Washington Dulles International Airport (9)

15. Detroit Metro Airport and Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport (7)

17. Boston-Logan International, Denver International and San Diego International airports (6)

20. Chicago O'Hare International Airport (5)

During a recent ABC News investigation, an iPad left behind at a security checkpoint at the Orlando airport was tracked as it moved 30 miles away to the home of the TSA officer last seen handling it.

Confronted two weeks later by ABC News, the TSA officer, Andy Ramirez, at first denied having the missing iPad, but ultimately turned it over after blaming his wife for taking it from the airport. Ramirez was later fired by the TSA.

The iPad was one of ten purposely left behind at TSA checkpoints at major airports with a history of theft by government screeners, as part of an ABC News investigation into the TSA's ongoing problem with theft of passenger belongings. The other nine iPads were returned to ABC News after being left behind.

The agency disputes that theft is a widespread problem, however, saying the number of officers fired "represents less than one-half of one percent of officers that have been employed" by TSA.

Hearing on hold for accused USS bomber

By Ben Fox Associated Press Tue Oct 23, 2012 9:21 PM

KINGSTON, Jamaica -- A dispute over whether a defendant must be present during a military tribunal brought proceedings to a halt Tuesday in the case of a Guantanamo prisoner accused in the attack on the Navy destroyer the USS Cole.

Defendant Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, 47, boycotted the pretrial motions hearing to protest the use of belly chains to move him from his cell at the Guantanamo Bay prison.

Prosecutors wanted al-Nashiri brought to court to explain his reasoning on the record before any discussion of other motions in the case. The defense objected, saying any use of force could traumatize a man who they say was tortured in U.S. custody.

Complicating matters was Tropical Storm Sandy, which was forecast to grow into a hurricane as it heads north in the Caribbean Sea and possibly force the evacuation of the U.S. base in Cuba.

The judge, Army Col. James Pohl, decided after more than 90 minutes of debate that al-Nashiri must come to court Wednesday.

“Tomorrow, weather permitting, your client is coming,” Pohl told the defense team, before the hearing was adjourned for the rest of the day.

Whether a defendant must attend sessions of the tribunal has been a recurring theme with al-Nashiri, who is accused of orchestrating the deadly 2000 bombing of the USS Cole in Yemen, as well as in the case of five Guantanamo prisoners charged in the Sept. 11 attacks.

Pohl, who presides over both cases, has previously ruled that defendants have a right to be absent from pretrial proceedings just as they have a right to be present for them.

He has not said yet whether they must attend their actual trials, which in both cases are not expected to start for at least a year. He has signaled he will likely require them to be in court once a jury is convened.

Prosecutors want the accused present for all proceedings, in part to eliminate any doubts about why they were absent that could later provide grounds for an appeal.

“The accused has to come to ensure the integrity of the trial,” the chief prosecutor, Army Brig. Gen. Mark Martins, said of al-Nashiri.

Al-Nashiri faces charges that include terrorism and murder in a special tribunal for wartime offenses known as a military commission for allegedly orchestrating the bombing of the USS Cole, an attack that killed 17 sailors and wounded 37. He is also accused of setting up attacks on two other vessels. He could get the death penalty if convicted.

Targeted killing is now so routine that the Obama administration has spent much of the past year codifying and streamlining the processes that sustain it.

The only question I have is when will the President allow the DEA to add names of suspected drug dealers to his murder list.

Of course first it will only be suspected drug dealers in foreign countries, then over time suspected drug dealers in America will be added to the list.

Plan for hunting terrorists signals U.S. intends to keep adding names to kill lists

By Greg Miller, Published: October 23

Editor’s note: This project, based on interviews with dozens of current and former national security officials, intelligence analysts and others, examines evolving U.S. counterterrorism policies and the practice of targeted killing. This is the first of three stories.

Over the past two years, the Obama administration has been secretly developing a new blueprint for pursuing terrorists, a next-generation targeting list called the “disposition matrix.”

The matrix contains the names of terrorism suspects arrayed against an accounting of the resources being marshaled to track them down, including sealed indictments and clandestine operations. U.S. officials said the database is designed to go beyond existing kill lists, mapping plans for the “disposition” of suspects beyond the reach of American drones.

Although the matrix is a work in progress, the effort to create it reflects a reality setting in among the nation’s counterterrorism ranks: The United States’ conventional wars are winding down, but the government expects to continue adding names to kill or capture lists for years.

Among senior Obama administration officials, there is a broad consensus that such operations are likely to be extended at least another decade. Given the way al-Qaeda continues to metastasize, some officials said no clear end is in sight.

“We can’t possibly kill everyone who wants to harm us,” a senior administration official said. “It’s a necessary part of what we do. . . . We’re not going to wind up in 10 years in a world of everybody holding hands and saying, ‘We love America.’ ”

That timeline suggests that the United States has reached only the midpoint of what was once known as the global war on terrorism. Targeting lists that were regarded as finite emergency measures after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, are now fixtures of the national security apparatus. The rosters expand and contract with the pace of drone strikes but never go to zero.

Meanwhile, a significant milestone looms: The number of militants and civilians killed in the drone campaign over the past 10 years will soon exceed 3,000 by certain estimates, surpassing the number of people al-Qaeda killed in the Sept. 11 attacks.

The Obama administration has touted its successes against the terrorist network, including the death of Osama bin Laden, as signature achievements that argue for President Obama’s reelection. The administration has taken tentative steps toward greater transparency, formally acknowledging for the first time the United States’ use of armed drones.